The Triton compiler aims to generate performance-portable code and runtime across hardware for AI kernels. To maintain compiler-generated code SOTA, the Triton developer community has been driving improvements around operator scheduling, memory allocation, layouts and management – both at the Triton DSL-level and at lower levels (e.g., Gluon and TLX).

As kernels and the space of their optimizations, and accelerator hardware, get rapidly complex over time, kernel authors and maintainers have a hard time keeping SOTA performance. Warp specialization has become a popular technique to improve kernel performance on GPUs out-of-the-box – the key idea is to have specialized code paths for each warp instead of the same code. This reduces performance hits due to control flow divergence, improves latency hiding and makes better use of hardware units on the GPU.

Warp Specialization is implemented in the compiler as lowering passes that specialize operations at JIT timescales, by searching the space of compute and memory management, scheduling, specialization to underlying hardware units and synchronization. Generating optimal warp specialized code to hit hardware roofline performance is a combinatorial problem.

Warp Specialization is a foundational infrastructure for many use cases. It helps kernel authors focus on the algorithmic optimizations, and not worry about the “how,” especially important as kernels get complex. It can specialize in the structure of the hardware topology and for workload heterogeneity. It supports specializing complex kernels and optimizations, including large fused kernels (“megakernels”).

In this post, we outline the current design of Warp Specialization in Triton (“autoWS”) and discuss our plans for the future. We are going to build this with the Triton developer community and invite feedback on the plan laid out in the post.

Warp Specialization Today

Note on implementation: autoWS has been built on top of OSS Triton. It is actively being developed in Meta’s OSS mirrorfacebookexperimental/triton, and has been partly upstreamed. autoWS can be enabled via tuning configurations (warp_specialize=True as part of ForOp), for both handwritten, TorchInductor and Helion-generated kernels. The compiler support in autoWS is limited and experimental, and we are working on generalizing it (details in roadmap below).

@triton.jit

def mykernel(...):

...

for start_n in tl.range(lo, hi, BLOCK_N,

warp_specialize=warp_specialize):

…

The compiler specializes code paths for each warp by partitioning the code paths (operators and data) inside the warp_specialize code regions, to optimize for control flow divergence, latency hiding and utilizing specialized hardware units – while preserving the correctness and numerics specified by the kernel code.

Current and new GPU architectures are increasingly complex pipelines, and need sophisticated compiler support for hitting roofline performance from increasingly complex kernels. The current autoWS implementation supports Hopper and Blackwell accelerators. We start with a high-level overview of the current autoWS design.

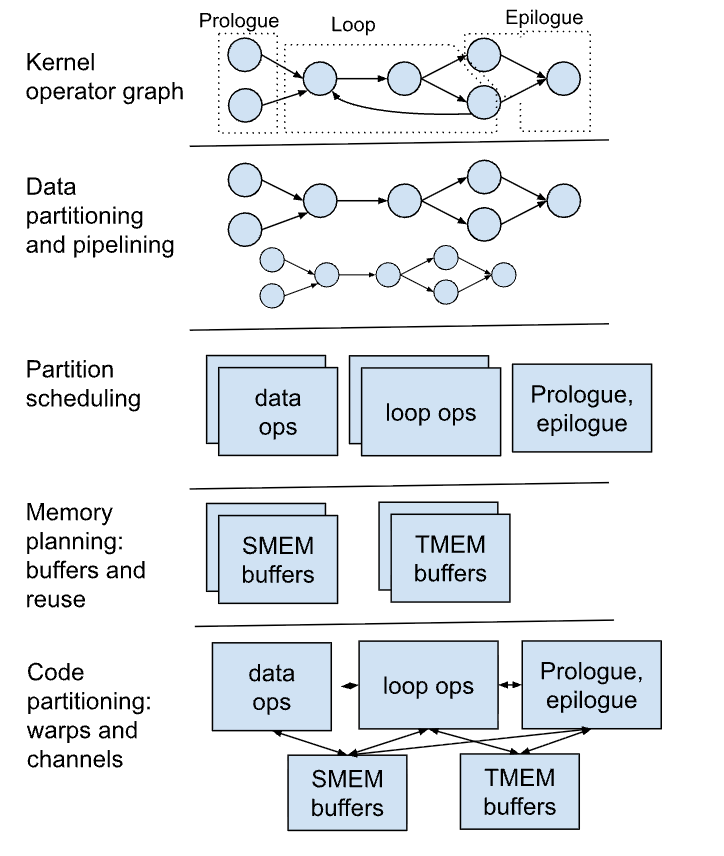

Warp specialization uses the following passes (in order):

- Data partitioning to have more GEMMs/ops to schedule in order to fully overlap resource usage

- Create a software pipeline (SWP) schedule based on heuristics and pass the decisions via attributes (Loop Scheduler)

- Partition the code into different warp partitions (Partition Scheduler) – decisions are passed via attributes

- Analyze and create communication buffers between the partitions (Buffer Creation), where buffers can be in either shared memory (SMEM) or tensor memory (TMEM) (for newer generations of NVIDIA accelerators).

- Make decisions around copies of buffers and buffer reuse (Memory Planner) – decisions are passed via attributes on buffer allocation.

- Create producer-consumer channels that encapsulate data flow and synchronization between partitions. Correctly lower the channel into buffer and barrier ops, split code into multiple warp partitions (Code Partitioner)

The decision-making passes include Loop Scheduler, Partition Scheduler, heuristics in buffer creation, where we choose to put a channel in either SMEM or TMEM, and memory planner.

Partition Scheduler. The Partition Scheduler partitions the code into one or more warp partitions and passes the partitions as op attributes. It currently uses simple heuristics and is based on the NVIDIA warp specialization in Triton. Examples of partitioning strategies include the currently supported compute partitions (e.g., Gen5 ops for MMA on tensor cores), data partitions (TMA loads) and epilogue and correction partitions; and (future work) mixed partitions (CUDA ops inside data partitions), partitioning/mixing TMA loads, hardware SFU ops and atomic adds with compute. After warp partitions are formed, data communication between partitions is set up using buffers/channels.

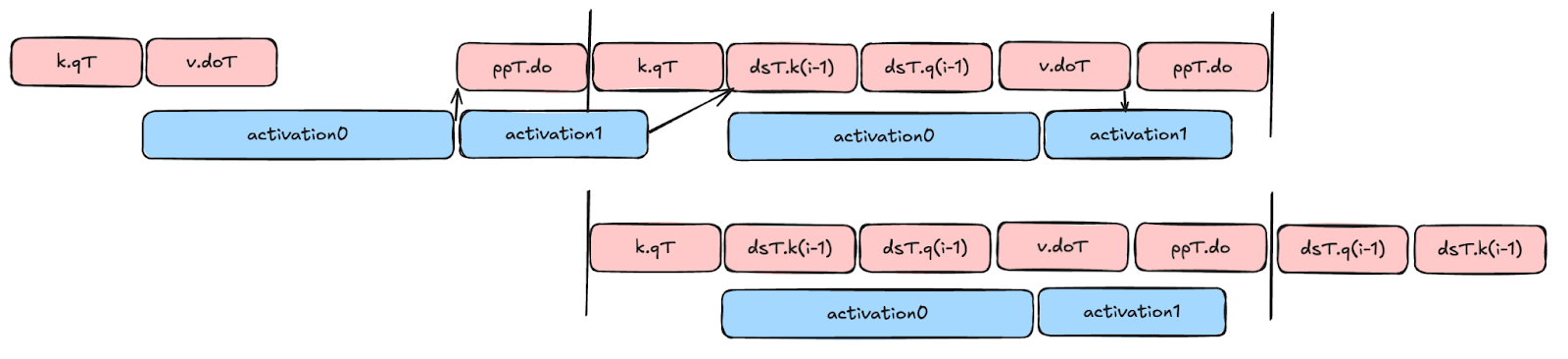

Software Pipelining (SWP) Scheduler. We modify the SWP scheduler to leverage the data parallelism produced by data partitioning. The modified scheduler reduces time waiting for data by reordering dependent operations maximally apart in the loop and replacing them with the data-independent copies. An example of flash attention’s forward pass is shown below.

| Before SWP: | After SWP: |

def dp_fa_fwd(...): ... for (...) qk1 = tl.dot(q1, k) qk2 = tl.dot(q2, k) p1 = softmax(qk1) p2 = softmax(qk2) acc1 = tl.dot(p1, v) acc2 = tl.dot(p2, v) |

def dp_fa_fwd(...): ... qk1 = tl.dot(q1, k0) qk2_prev = tl.dot(q2, k0) p1 = softmax(qk0) acc1 = tl.dot(p1, v0) for (...) qk1 = tl.dot(q1, k) p2 = softmax(qk2_prev) acc2 = tl.dot(p2, v_prev) qk2_prev = tl.dot(q2, k) p1 = softmax(qk0) acc1 = tl.dot(p1, v) p2 = softmax(qk2_prev) acc2 = tl.dot(p2, v_prev) |

In the above example, consecutive iterations of the attention forward loop are pipelined, overlapping two dot products and a softmax computation from different loop iterations.

The pipelining semantics are preserved through the warp specialization passes. Currently, this is implemented for forward passes of attention, as it is based primarily on independent chains of tl.dot. We plan to generalize the implementation.

Memory Planner. The memory planner decides how many buffers each channel uses and how channels should reuse buffers. Note that an earlier pass allocates TMEM or SMEM to channels during buffer creation.

Memory planner uses channel-aware liveness and dependency chain analysis to allocate and reuse TMEM and SMEM buffers between producer-consumer patterns. It classifies allocations based on each innermost loop; innermost loops get multi-buffering allocations. Operations in TMEM are prioritized by accumulator types (operand D, the accumulator that stores MMA result), size and live range.

Memory planner aggressively reuses allocated buffers if live ranges do not overlap. It reuses buffers along dependency chains on the same loop, or different loops within a partition. If a buffer overlaps with all allocated buffers and existing allocations cannot be reused, it allocates new space.

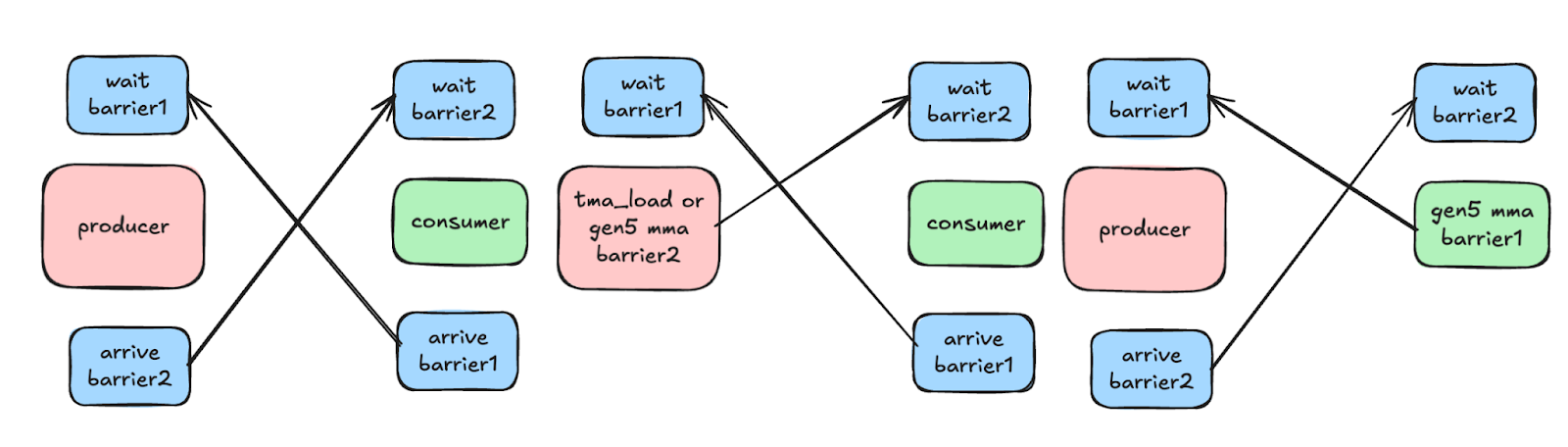

Code Partitioner. Once the kernel operations are partitioned and buffers are planned, the next step is to connect the partitions to set up the kernel computation. The code partitioner does small-scope instruction ordering and synchronization. One example of reordering is to reorder operations from different data partitions if they end up in the same warp partition, to reduce live range and register pressure.

The code partitioner sets up synchronization mechanisms as follows. For each channel, we assume that the source op and destination op are in the same scope and will be executed the same number of times. Code partitioner uses one accumulated index count to track the number of executions, and computes buffer index and phase based on the accumulated index count and number of buffers for the channel. Code partitioner uses two barriers for synchronization between source and destination of the channel. It can reuse existing barriers associated with TMA/gen5 GEMM if the source or destination comes from TMA/gen5, respectively.

Memory planner makes decisions around buffer reuses and annotates the allocation ops with buffer ID, offset, copy etc. If two channels have the same buffer ID, it uses the same memory allocation. When generating barrier ops for the channels, if two channels A and B reuse the same space, the code partitioner uses the same set of barriers and a single accumulated index count for both channels. The accumulated index counts the combined number of executions for source or destination op of both channels. This guarantees correctness: the channels are chained and use the right buffer index, or the correct synchronization is enforced between A and B.

The autoWS implementation demonstrated flash attention forward kernel performance close to hand-tuned low-level implementations [Triton Conference, 2025]. Our benchmarks with flash attention forward pass kernels across attention and sequence length configurations on B200 show TFLOPS numbers close to Gluon and cuDNN implementations, and 1.5-2x of stock Triton (cuDNN still leads by 10-20%). The autoWS benchmarks are based on Helion autotuning and ptxas advanced compiler configuration.

Short-Term Directions (< one year)

Profile-Guided Partition Scheduling

We plan to invest in profile-guided optimization as a future direction (see Future Directions below). We intend to start with a tactical but incremental step – to enable closer-to-roofline partitioning of operations within a kernel. We start with offline estimates of per-operator performance (e.g., TMEM and SMEM loads and stores), and per-region and e2e execution time. During partitioning, autoWS would estimate the communication overhead of op-to-op channels between partitions.

Profile-Guided SWP Scheduling

The current SWP scheduling can generate more roofline-optimal schedules by using runtime profiles. We plan to extend the SWP scheduler to use operator profiles with data dependency analysis to improve generated schedules. This could be using standard modulo scheduling with better support for outer loops (e.g., with loop flattening). We could find the closest-to-roofline schedule by autotuning cost-estimated top-ranking schedules.

Let’s consider the flash attention backward pass kernel as an example. We can construct the dependency graph and annotate each op with latency information. This enables compiler pipelining optimizations such as a modulo scheduling. We can also rank a few top schedules to autotune. The following figure visualizes a toy example of SWP schedule improvement for backward pass of flash attention, if the scheduler used latency profiles. The top part of the figure shows execution of operations without profile-based pipelining (arrows show data dependencies); with latency information, the compiler can “bin pack” execution of operations as shown in the bottom part.

Memory Planner Improvements

The memory planner needs to find an optimal set of channels in TMEM/SMEM allocations with buffer reuse, and this tends to be over a combinatorial search space (especially as kernel and hardware complexity increases). We are considering mechanisms to improve memory planning: user annotations at the DSL level to guide planning, and estimate the cost of a memory plan and autotune over selected plans.

Ping-Pong Scheduling

Ping-pong refers to enforcing exclusivity when scheduling long-running high-occupancy code regions that require critical hardware resources (e.g., SFUs, SMEM/TMEM). When these resources are contended, prioritizing the warp that produces the immediately needed data can significantly improve hardware utilization and kernel performance. We are working on a pass that identifies and schedules these critical sections (that executes prior to code partitioning and sets operator context).

We currently identify critical sections of operations using pattern matching for a limited set of operations (based on offline performance tuning experiments on hardware types). The pass identifies region boundaries using pre-defined rules (e.g., include memory operations for arithmetic operations). Barrier synchronization around critical sections could degrade performance – we currently expose ping-pong enablement for autotuning.

Region-based Explicit Subtitling

Subtiling can be a performance-optimizing transformation over a tiled program if tiling creates bottlenecks such as register pressure, bank conflicts and stalls. Authors can perform manual subtitling in kernel code today. If the subtiling region falls among multiple warp group partitions, the compiler needs to be improved to handle it correctly and use finer-grained synchronization to subdivide a channel into smaller channels. This unlocks improvements in producer-consumer pipelining – when a subset of a producer is done, the corresponding subset of the consumer can start. In order to make kernel authoring easier, we can add syntactic sugar for region-based subtiling, i.e., exposing the specification of the subtiling factor as an explicit region-level primitive for kernel authors in the DSL.

Debuggability and Tooling

Warp specialization can make it harder for model and kernel authors to debug numerics and performance issues, since it makes optimizing transformations to warp-granularity schedules, memory plans and layouts. We are building tooling and IR support to enable authors to debug kernel code generation and execution.

New tooling. We plan to convert Triton TTGIR to readable TLX kernels for easier debugging and further performance hand-tuning. To make the compiler decisions easy to understand for authors, we are building tooling to visualize warp specialized code, such as warp partitioning, dependency graphs with channels, memory allocation and planning decisions, and SWP schedules. We are exploring the possibility of adding interactive tooling for authors to make compile-time decisions and continue with the rest of the pass pipeline.

IR improvements. Our implementation currently does not use abstract representations for channels at IR level. We are looking at using upstream Triton’s aref as an additional abstraction. The aref pass pipeline has aref lowering right after aref insertion, and we plan to add support for aref to represent buffer reuse and delay the lowering so passes can take advantage of the abstraction.

Generality and Stability

We are working on generalizing the heuristics and stabilizing transformation passes to support a wider variety of kernels: flash attention backward, flex attention, jagged attention kernels, etc.

SOTA Hardware Specialization

Adding support for SOTA and emerging hardware features is necessary to hit roofline performance for kernels. We are adding support for features such as NVIDIA Blackwell’s Cluster Launch Control, distributed shared memory, multi-CTA, and on-device TMA descriptor pipelines; and AMD wave specialization, ping-pong and multi-stream scheduling. This is a continuous effort as we expect to support new hardware releases.

Future Directions

Model-based Global Optimization

Generating code that can reach roofline performance for a kernel and hardware type is a combinatorial search problem. We are exploring the use of cost models of the hardware and operations as a mechanism to prune the joint search space of partitioning and synchronization, scheduling, memory planning and tensor layouts. The cost model could be statically specified (e.g., operation latencies and hardware specification), or learned based on runtime benchmarking and profiling data. We plan to use the Triton-MPP (Multi Pass Profiler) to measure operation latencies from kernel benchmarking across hardware types and use the profiles to guide optimization passes.

Accurate cost models would enable the compiler to generate performant code for complex kernels for any hardware type. We are exploring building a global planner that can do joint optimization across scheduling, synchronization and memory management – by combining data dependency analysis and cost model. A global planner can output optimal SWP schedule, channel and buffer reuse configurations, operation partitioning and memory allocations.

Kernel/Operator Fusion and Megakernels

Kernel and operator fusion can significantly optimize model e2e performance by reducing GPU-CPU context switch overheads and improving memory locality and pressure. Getting fusion to work tends to be a combinatorial search across algorithmic, scheduling, tensor layout and memory planning dimensions. Megakernels take the kernel fusion idea to enable one or a few kernels for forward and backward pass computations in the model.

Kernel/operator fusion is done by PyTorch using algorithmic optimizations using Triton templates at Inductor level. While this works in many cases, it does not support fusions with user-defined Triton kernels. The Triton compiler could enable IR-level fusion between handwritten kernels and auto-generated kernels at a tile level. Further, specializing the lower-level operations inside the kernels could bring model workloads closer to roofline performance through joint algorithmic and performance optimization.

Our goal is to build aggressive fusion support over a collection of dependent or independent kernels. Fusing and tiling loops within and across kernels is a part of this goal. Needless to say, the algorithmic transformations should be provably correct.

Determinism for Numerics

We are looking at adding support for deterministic warp specialization, which would allow the kernel/model author to reason about and control the program specialization and compiler decisions. The author would be able to leverage numerical support in the Triton and PyTorch DSLs as levers for numerical determinism and stability. We covered other aspects of determinism in the short-term directions section above.

Language Support

Language support enables the author to pass domain knowledge of the expected workload and operations to the compiler (to generate performant code), and at the same time, control and reason about compiler decisions and code transformations. We are exploring language support that includes DSL abstractions that separate computation from data (e.g., Cypress, PLDI 2025; Halide, PLDI 2013) and express the “task graph” and schedules independently from data properties; and authoring hints that enable the compiler to specialize program regions and operations closer to roofline. Declarative languages for specification of schedules, data properties and specialization are a potential direction. Language choices tend to be broad and we are looking for feedback and suggestions from the community.

End Note

In this post, we covered the current state of autoWS warp specialization in Triton, and our roadmap and thoughts to improve the Triton compiler, tools and language support. We invite feedback and suggestions from the community on our roadmap and your thoughts on how to make autoWS better.

Acknowledgements: Thank you to our leadership team Alexey Loginov, Bill Yoshimi, Ian Barber and Parthiv Patel; and the Triton team and Meta-internal customers for supporting autoWS development. We thank NVIDIA and OpenAI for collaboration on autoWS.