Introduction

Among the many things Disney Media & Entertainment Distribution (DMED) is responsible for, is the management and distribution of a huge array of media assets including news, sports, entertainment and features, episodic programs, marketing and advertising and more.

Our team focuses on media annotation as part of DMED Technology’s content platforms group. In our day-to-day work, we automatically analyze a variety of content that constantly challenges the efficiency of our machine learning workflow and the accuracy of our models.

Several of our colleagues recently discussed the workflow efficiencies that we achieved by switching to an end-to-end video analysis pipeline using PyTorch, as well as how we approach animated character recognition. We invite you to read more about both in this previous post.

While the conversion to an end-to-end PyTorch pipeline is a solution that any company might benefit from, animated character recognition was a uniquely-Disney concept and solution.

In this article we will focus on activity recognition, which is a general challenge across industries — but with some specific opportunities when leveraged in the media production field, because we can combine audio, video, and subtitles to provide a solution.

Experimenting with Multimodality

Working on a multimodal problem adds more complexity to the usual training pipelines. Having multiple information modes for each example means that the multimodal pipeline has to have specific implementations to process each mode in the dataset. Usually after this processing step, the pipeline has to merge or fuse the outputs.

Our initial experiments in multimodality were completed using the MMF framework. MMF is a modular framework for vision and language multimodal research. MMF contains reference implementations of state-of-the-art vision and language models and has also powered multiple research projects at Meta AI Research (as seen in this poster presented in PyTorch Ecosystem Day 2020). Along with the recent release of TorchMultimodal, a PyTorch library for training state-of-the-art multimodal models at scale, MMF highlights the growing interest in Multimodal understanding.

MMF tackles this complexity with modular management of all the elements of the pipeline through a wide set of different implementations for specific modules, ranging from the processing of the modalities to the fusion of the processed information.

In our scenario, MMF was a great entry point to experiment with multimodality. It allowed us to iterate quickly by combining audio, video and closed captioning and experiment at different levels of scale with certain multimodal models, shifting from a single GPU to TPU Pods.

Multimodal Transformers

With a workbench based on MMF, our initial model was based on a concatenation of features from each modality evolving to a pipeline that included a Transformer-based fusion module to combine the different input modes.

Specifically, we made use of the fusion module called MMFTransformer, developed in collaboration with the Meta AI Research team. This is an implementation based on VisualBERT for which the necessary modifications were added to be able to work with text, audio and video.

Despite having decent results with the out-of-box implementation MMFTransformer, we were still far from our goal, and the Transformers-based models required more data than we had available.

Searching for less data-hungry solutions

Searching for less data-hungry solutions, our team started studying MLP-Mixer. This new architecture has been proposed by the Google Brain team and it provides an alternative to well established de facto architectures like convolutions or self-attention for computer vision tasks.

MLP-Mixer

The core idea behind mixed variations consists of replacing the convolutions or self-attention mechanisms used in transformers with Multilayer Perceptrons. This change in architecture favors the performance of the model in high data regimes (especially with respect to the Transformers), while also opening some questions regarding the inductive biases hidden in the convolutions and the self-attention layers.

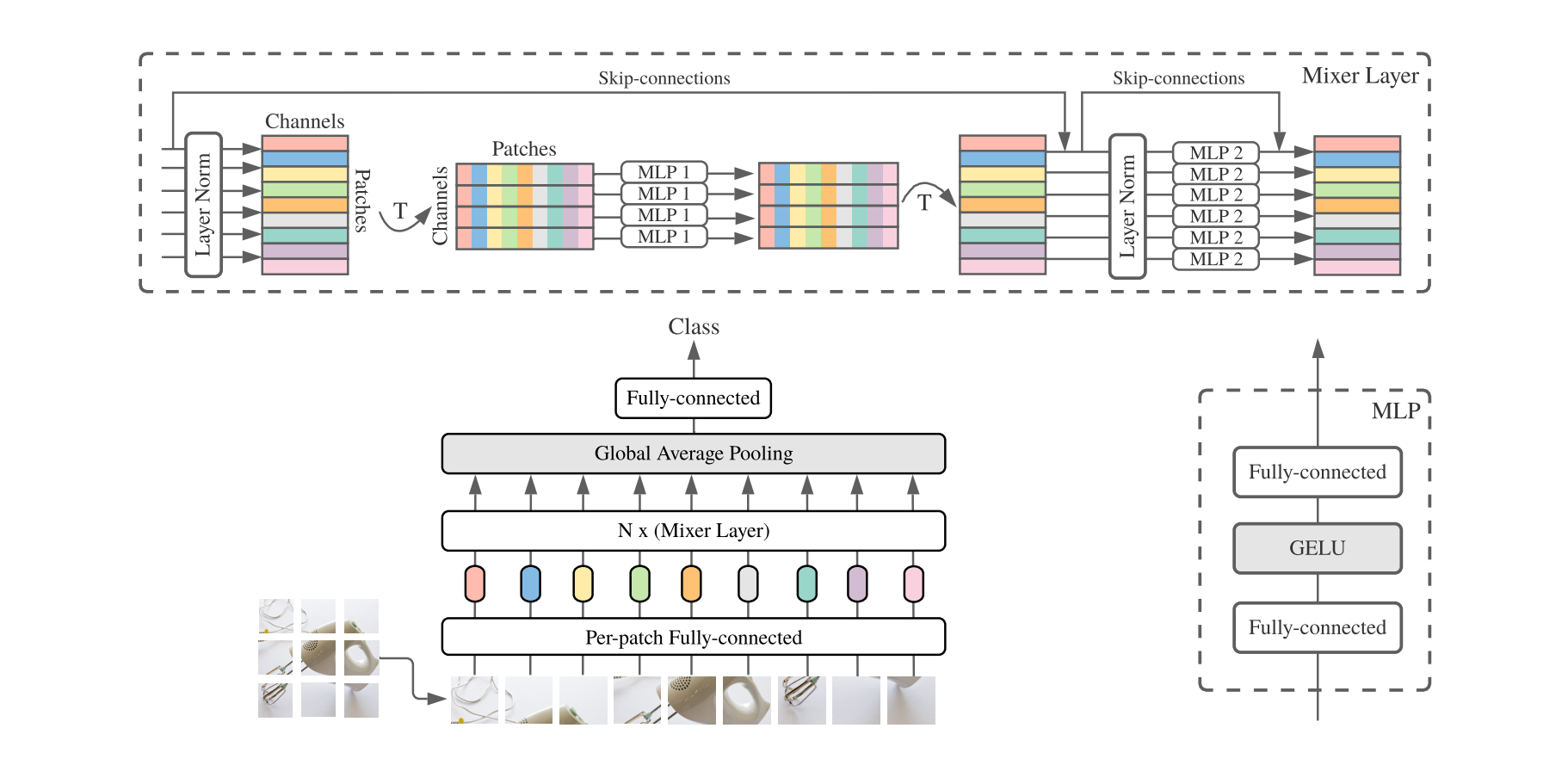

Those proposals perform great in solving image classification tasks by splitting the image in chunks, flattening those chunks into 1D vectors and passing them through a sequence of Mixer Layers.

Inspired by the advantages of Mixer based architectures, our team searched for parallelisms with the type of problems we try to solve in video classification: specifically, instead of a single image, we have a set of frames that need to be classified, along with audio and closed captioning in the shape of new modalities.

Activity Recognition reinterpreting the MLP-Mixer

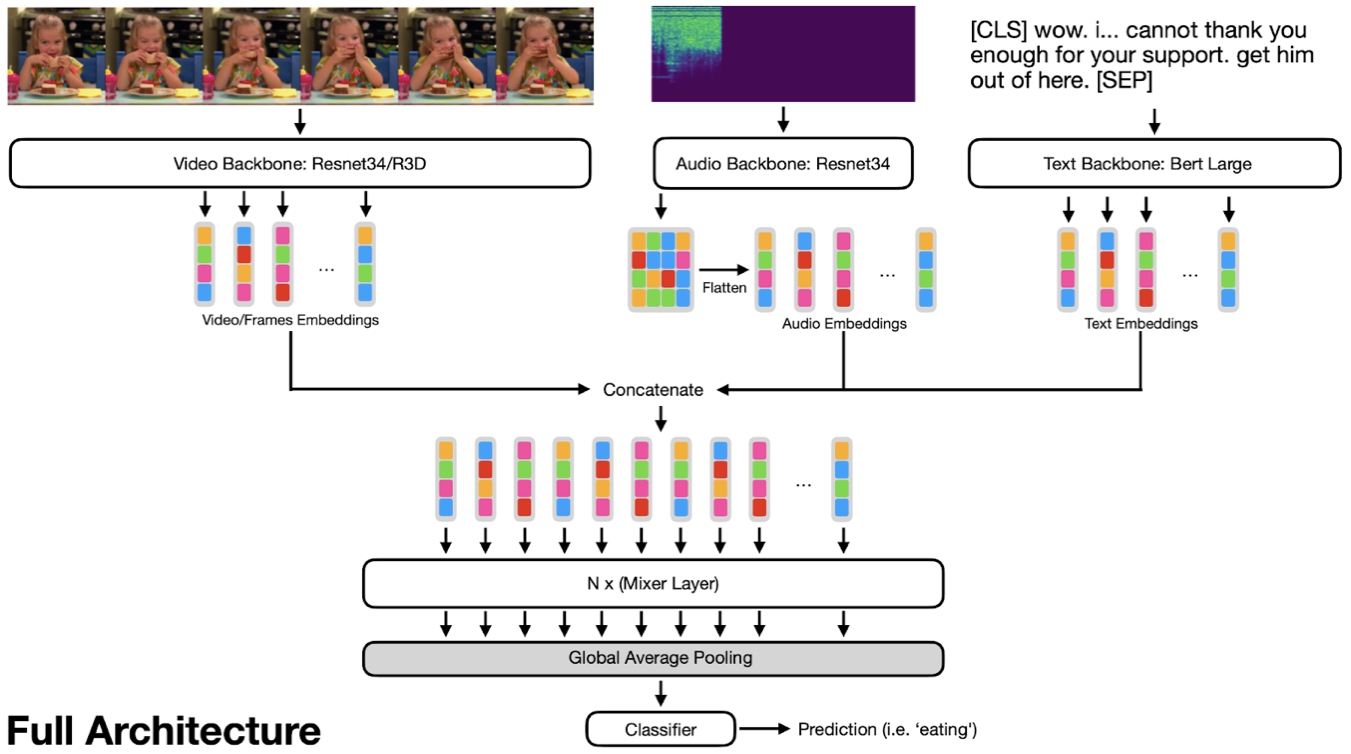

Our proposal takes the core idea of the MLP-Mixer — using multiple multi-layer perceptrons on a sequence and transposed sequence and extends it into a Multi Modal framework that allows us to process video, audio & text with the same architecture.

For each of the modalities, we use different extractors that will provide embeddings describing the content. Given the embeddings of each modality, the MLP-Mixer architecture solves the problem of deciding which of the modalities might be the most important, while also weighing how much each modality contributes to the final labeling.

For example, when it comes to detecting laughs, sometimes the key information is in audio or in the frames, and in some of the cases we have a strong signal in the closed caption.

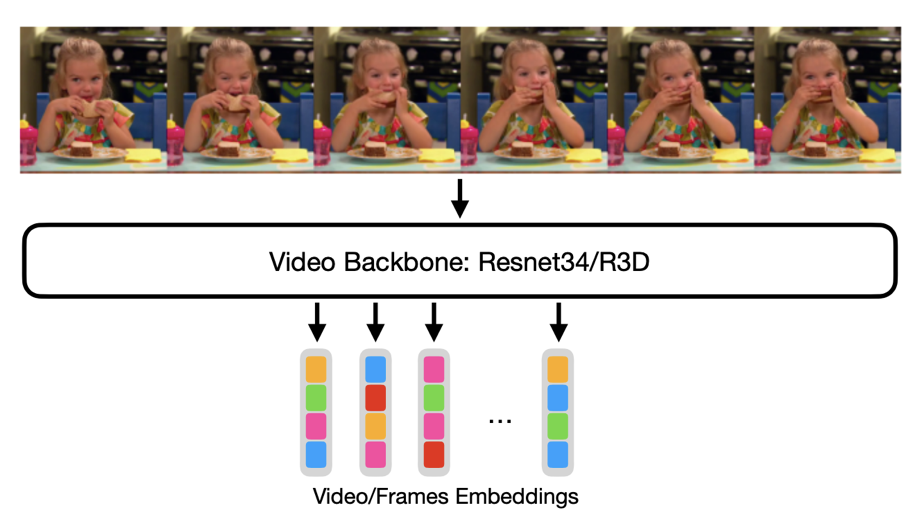

We tried processing each frame separately with a ResNet34 and getting a sequence of embeddings and by using a video-specific model called R3D, both pre-trained on ImageNet and Kinetics400 respectively.

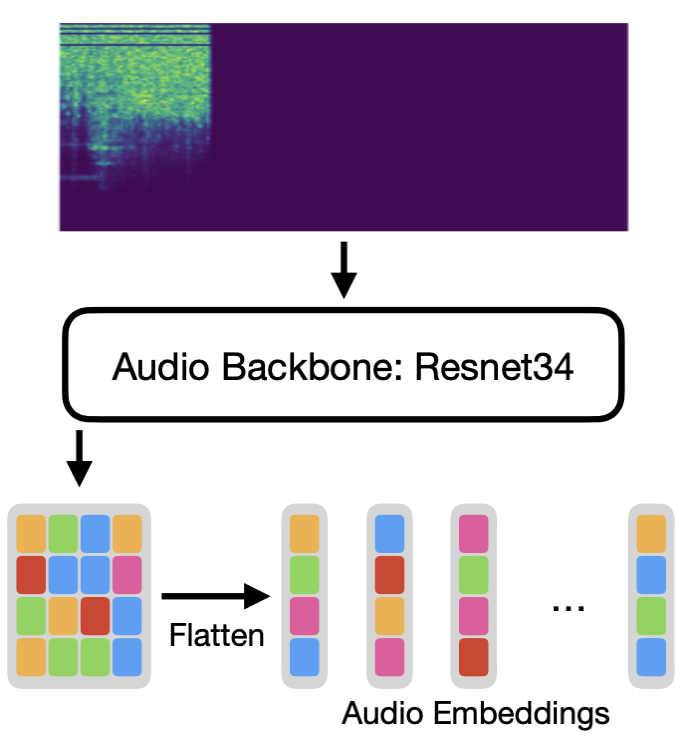

To process the audio, we use the pretrained ResNet34, and we remove the final layers to be able to extract 2D embeddings from the audio spectrograms (for 224×224 images we end up with 7×7 embeddings).

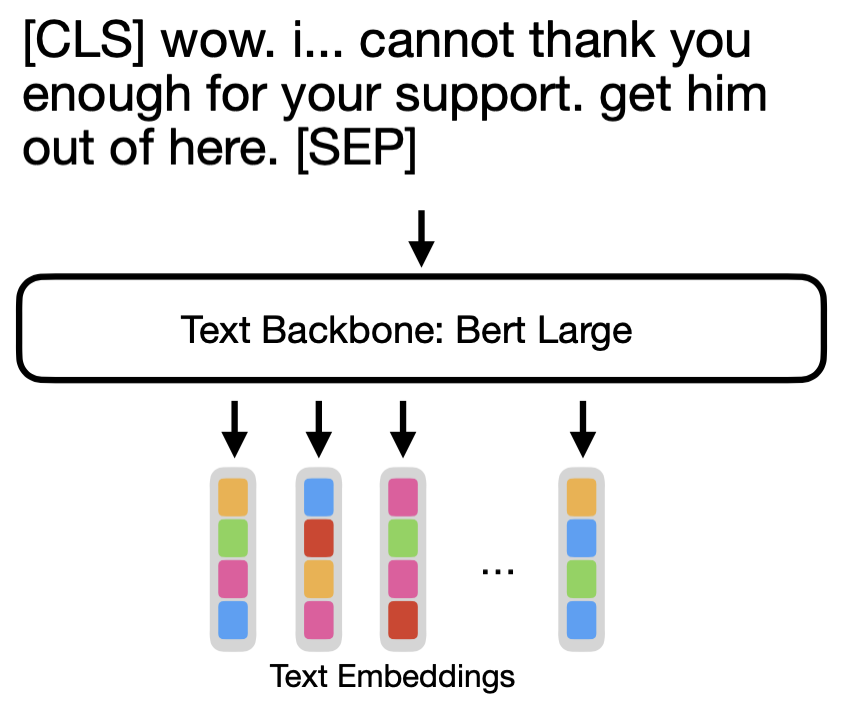

For closed captioning, we are using a pre-trained BERT-large, with all layers frozen, except for the Embeddings & LayerNorms.

Once we have extracted the embedding from each modality, we concatenate them into a single sequence and pass it through a set of MLP-Mixer blocks; next we use average pooling & a classification head to get predictions.

Our experiments have been performed on a custom, manually labeled dataset for activity recognition with 15 classes, which we know from experiments are hard and cannot all be predicted accurately using a single modality.

These experiments have shown a significant increase in performance using our approach, especially in a low/mid-data regime (75K training samples).

When it comes to using only Text and Audio, our experiments showed a 15 percent improvement in accuracy over using a classifier on top of the features extracted by state-of-the-art backbones.

Using Text, Audio and Video we have seen a 17 percent improvement in accuracy over using Meta AIFacebook’s MMF Framework, which uses a VisualBERT-like model to combine modalities using more powerful state of the art backbones.

Currently, we extended the initial model to cover up to 55 activity classes and 45 event classes. One of the challenges we expect to improve upon in the future is to include all activities and events, even those that are less frequent.

Interpreting the MLP-Mixer mode combinations

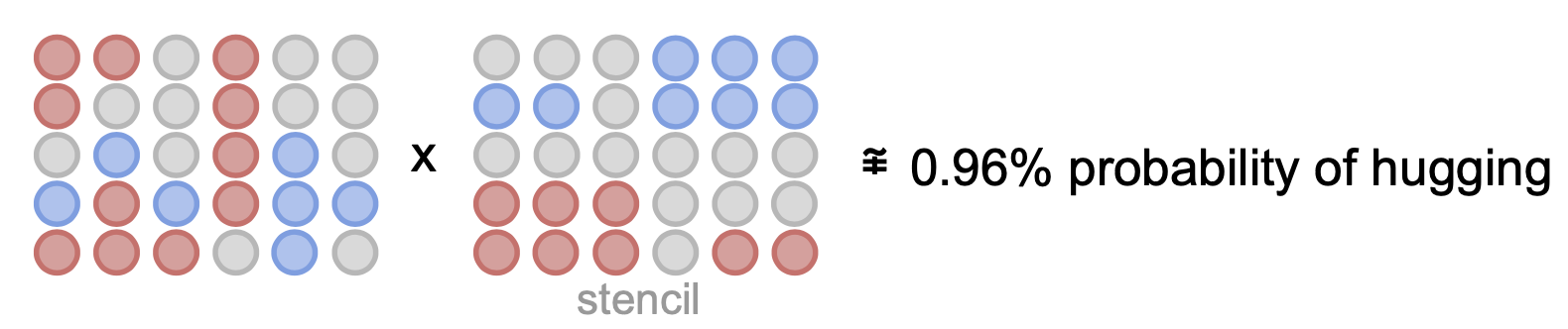

An MLP-Mixer is a concatenation of MultiLayer Perceptrons. This can be, very roughly, approximated to a linear operation, in the sense that, once trained, the weights are fixed and the input will directly affect the output.

Once we assume that approximation, we also assume that for an input consisting of NxM numbers, we could find a NxM matrix that (when multiplied elementwise) could approximate the predictions of the MLP-Mixer for a class.

We will call this matrix a stencil, and if we have access to it, we can find what parts of the input embeddings are responsible for a specific prediction.

You can think of it as a punch card with holes in specific positions. Only information in those positions will pass and contribute to a specific prediction. So we can measure the intensity of the input at those positions.

Of course, this is an oversimplification, and there won’t exist a unique stencil that perfectly represents all of the contributions of the input to a class (otherwise that would mean that the problem could be solved linearly). So this should be used for visualization purposes only, not as an accurate predictor.

Once we have a set of stencils for each class, we can effortlessly measure input contribution without relying on any external visualization techniques.

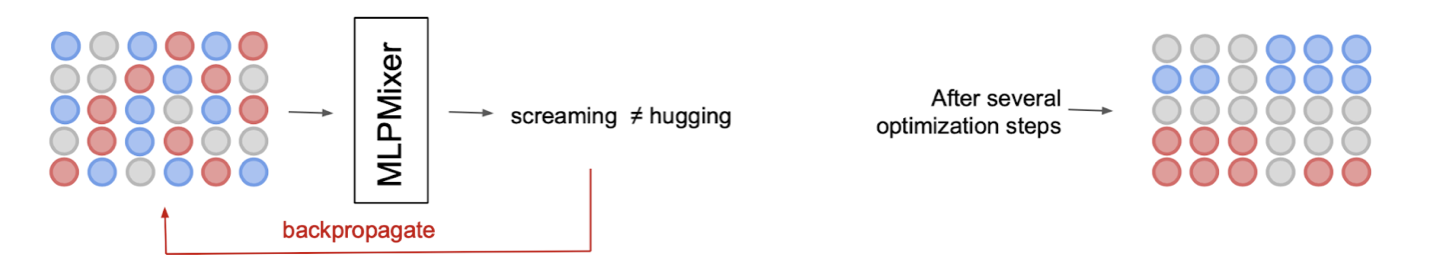

To find a stencil, we can start from a “random noise” stencil and optimize it to maximize the activations for a specific class by just back-propagating through the MLP-Mixer.

By doing this we can end up with many valid stencils, and we can reduce them to a few by using K-means to cluster them into similar stencils and averaging each cluster.

Using the Mixer to get the best of each world

MLP-Mixer, used as an image classification model without convolutional layers, requires a lot of data, since the lack of inductive bias – one of the model’s good points overall – is a weakness when it comes to working in low data domains.

When used as a way to combine information previously extracted by large pretrained backbones (as opposed to being used as a full end-to-end solution), they shine. The Mixer’s strength lies in finding temporal or structural coherence between different inputs. For example, in video-related tasks we could extract embeddings from the frames using a powerful, pretrained model that understands what is going on at frame level and use the mixer to make sense of it in a sequential manner.

This way of using the Mixer allows us to work with limited amounts of data and still get better results than what was achieved with Transformers. This is because Mixers seem to be more stable during training and seem to pay attention to all the inputs, while Transformers tend to collapse and pay attention only to some modalities/parts of the sequence.

Acknowledgements: We would like to thank the Meta AI Research and Partner Engineering teams for this collaboration.