Abstract

The Hopper (H100) GPU architecture, billed as the “first truly asynchronous GPU”, includes a new, fully asynchronous hardware copy engine for bulk data movement between global and shared memory called Tensor Memory Accelerator (TMA). While CUTLASS has built-in support for TMA via its asynchronous pipeline paradigm, Triton exposes TMA support via an experimental API.

In this post, we provide a deeper dive into the details of how TMA works, for developers to understand the new async copy engine. We also show the importance of leveraging TMA for H100 kernels by building a TMA enabled FP8 GEMM kernel in Triton, which delivers from 1.4-2.2x performance gains over cuBLAS FP16 for small-to-medium problem sizes. Finally, we showcase key implementation differences between Triton and CUTLASS that may account for reports of performance regressions with TMA in Triton. We open source our implementation for reproducibility and review at https://github.com/pytorch-labs/applied-ai/tree/main/kernels

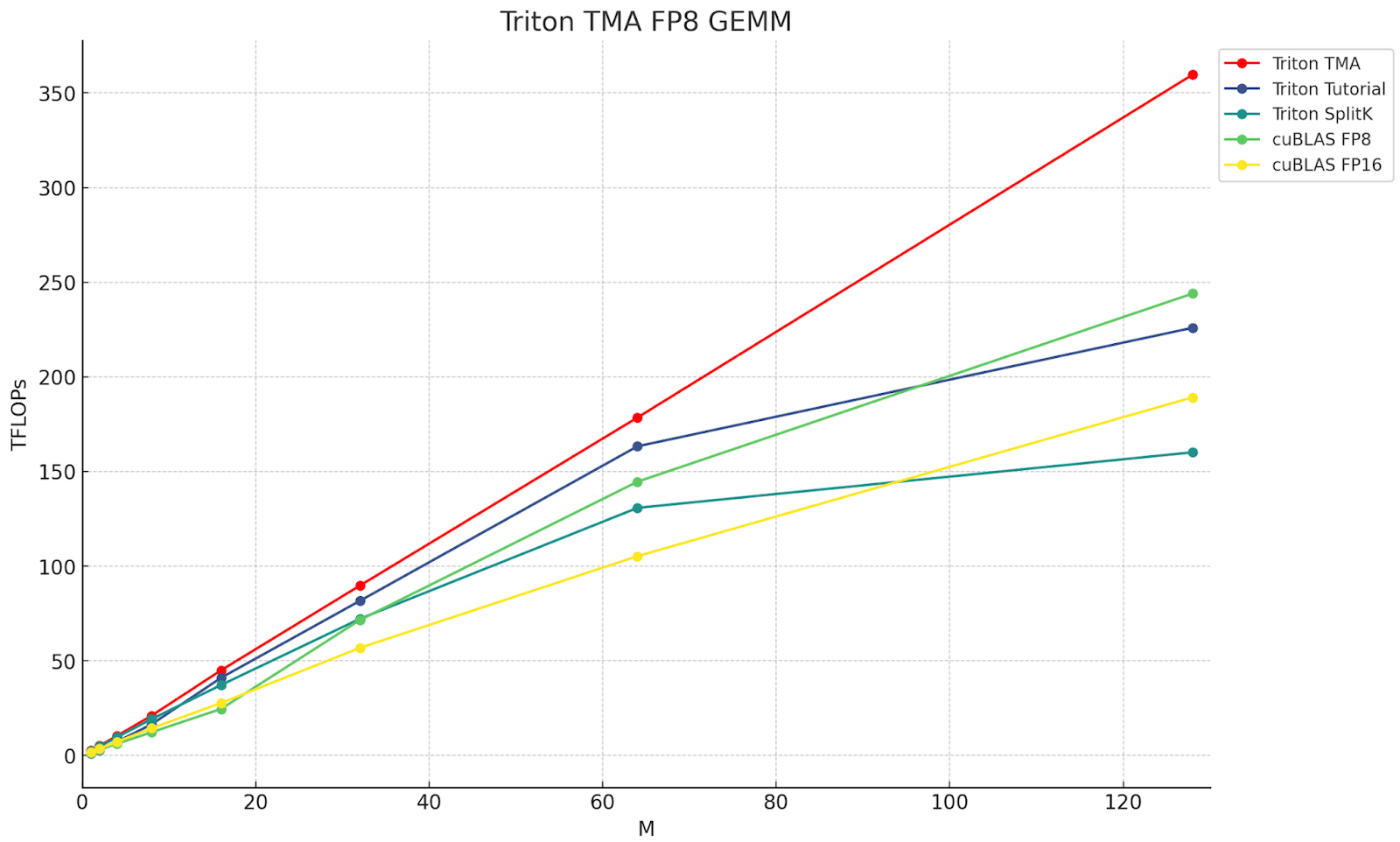

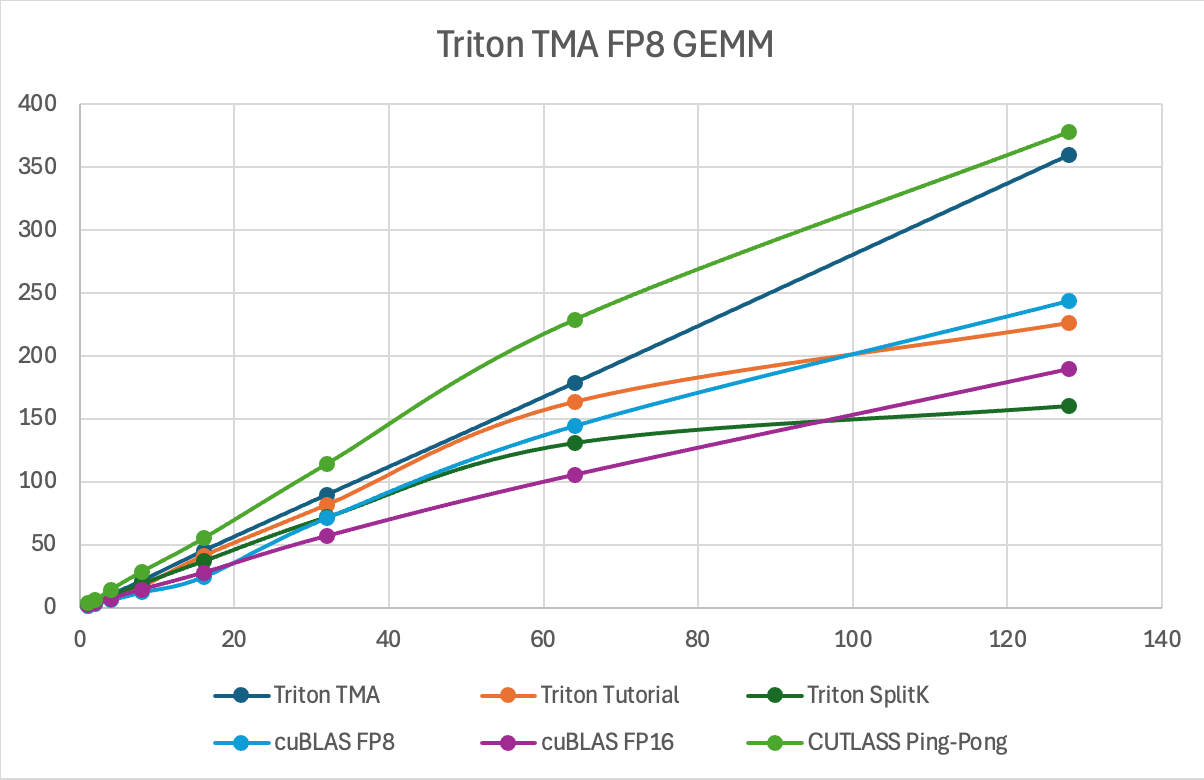

Figure 1. The throughput in TFLOPs of various Triton and cuBLAS FP8 and FP16 kernels, for M=M, N=4096, K=4096. The red line is the Triton TMA, which showcases the advantages of leveraging TMA.

TMA Background

TMA is an H100 hardware addition that allows applications to asynchronously and bi-directionally transfer 1D-5D tensors between GPU global and shared memory. In addition, TMA can also transfer the same data to not just the calling SM’s shared memory, but to other SM’s shared memory if they are part of the same Thread Block Cluster. This is termed ‘multicast’.

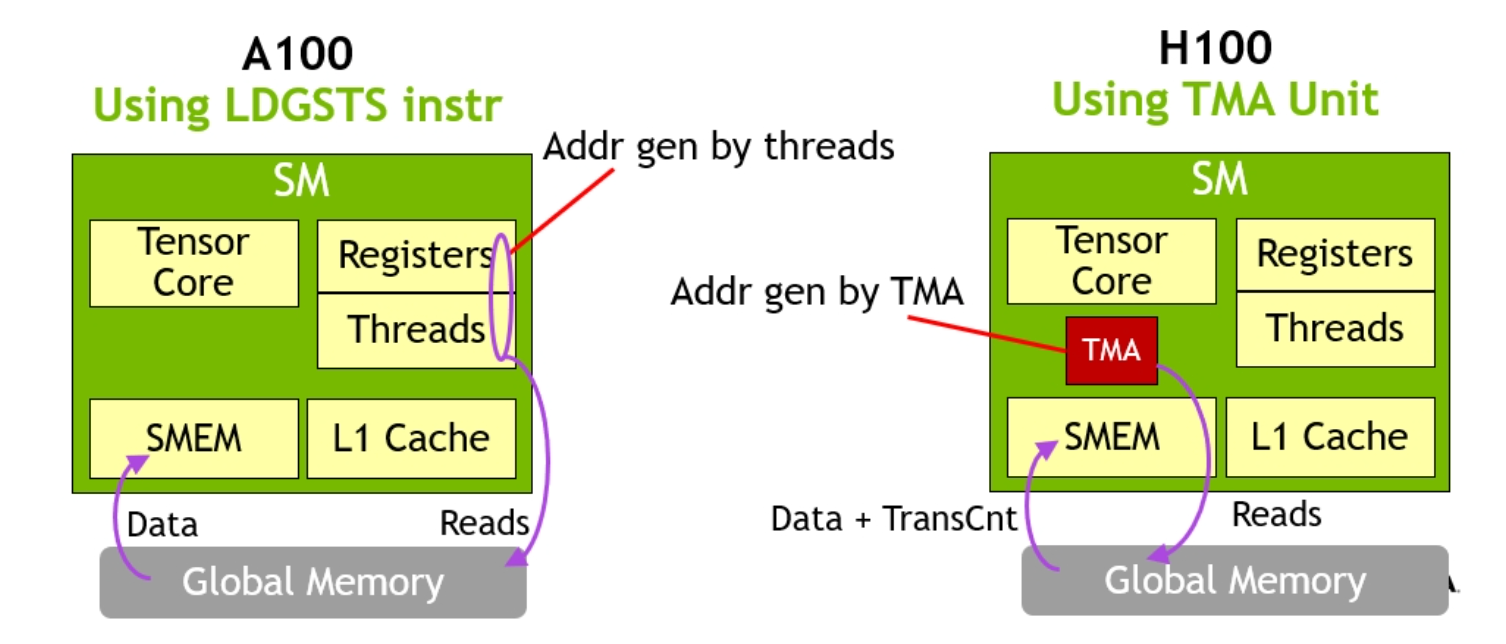

TMA is very lightweight as only a single thread is needed to kick off a TMA transfer. By moving data directly from GMEM (global) to SMEM (shared), this avoids earlier GPU requirements of using registers for moving data between different memory spaces.

Figure 2. A100-style data movement vs H100 with TMA. TMA hardware eliminates the need for a large amount of threads and registers participating in bulk data transfers. (Image credit Nvidia)

A single thread can issue large data movement instructions, allowing the majority of a given thread block to continue working on other instructions while data is in-flight. Combined with asynchronous pipelining, this allows memory transfers to be easily hidden and ensure the majority of any given thread block cluster can focus on computational task.

This lightweight invocation for data movement enables the creation of warp-group specialized kernels, where warp-groups take on different roles, namely producers and consumers. Producers elect a leader thread that fires off TMA requests, which are then asynchronously coordinated with the consumer (MMA) warp-groups via an arrival barrier. Consumers then process the data using warp-group MMA, and signal back to the producers when they have finished reading from the SMEM buffer and the cycle repeats.

Further, within threadblock clusters, producers can lower their max register requirements since they are only issuing TMA calls, and effectively transfer additional registers to MMA consumers, which helps to alleviate register pressure for consumers.

In addition, TMA handles the address computation for the shared memory destination where the data requested should be placed. This is why calling threads (producers) can be so lightweight.

To ensure maximum read access speed, TMA can lay out the arriving data based on swizzling instructions, to ensure the arriving data can be read as fast as possible by consumers, as the swizzling pattern helps avoid shared memory bank conflicts.

Finally for TMA instructions that are outgoing, or moving data from SMEM to GMEM, TMA can also include reduction operations (add/min/max) and bitwise (and/or) operations.

TMA usage in Triton

Pre-Hopper Load:

offs_m = pid_m*block_m + tl.arange(0, block_m)

offs_n = pid_n*block_n + tl.arange(0, block_n)

offs_k = tl.arange(0, block_k)

a_ptrs = a_ptr + (offs_am[:, None]*stride_am + offs_k[None, :]*stride_ak)

b_ptrs = b_ptr + (offs_k[:, None]*stride_bk + offs_bn[None, :]*stride_bn)

a = tl.load(a_ptrs)

b = tl.load(b_ptrs)

Figure 3. Traditional style bulk load from global to shared memory in Triton

In the above Triton example showing a pre-Hopper load, we see how the data for tensors a and b are loaded by each thread block computing global offsets (a_ptrs, b_ptrs) from their relevant program_id (pid_m, pid_n, k) and then making a request to move blocks of memory into shared memory for a and b.

Now let’s examine how to perform a load using TMA in Triton.

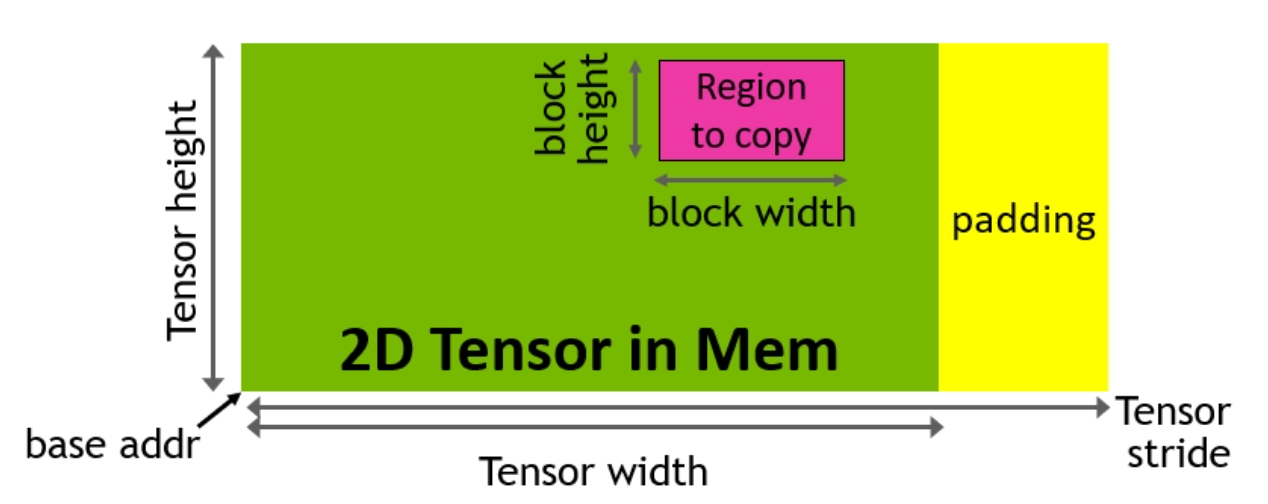

The TMA instruction requires a special data structure called a tensor map, in contrast to the above where we directly pass pointers to global memory. To build the tensor map, we first create a TMA descriptor on the CPU. The descriptor handles the creation of the tensor map by using the cuTensorMapEncode API. The tensor map holds metadata such as the global and shared memory layout of the tensor and serves as a compressed representation of the structure of the multi-dimensional tensor stored in global memory.

Figure 4. TMA address generation via a copy descriptor (Image credit: Nvidia)

The TMA descriptor holds the tensor’s key properties:

- Base Pointer

- Shape and Block Size

- Datatype

The TMA descriptor is created on the host before the kernel, and then moved to device by passing the descriptor to a torch tensor. Thus, in Triton, the GEMM kernel receives a global pointer to the tensor map.

Triton Host Code

desc_a = np.empty(TMA_SIZE, dtype=np.int8)

desc_b = np.empty(TMA_SIZE, dtype=np.int8)

desc_c = np.empty(TMA_SIZE, dtype=np.int8)

triton.runtime.driver.active.utils.fill_2d_tma_descriptor(a.data_ptr(), m, k, block_m, block_k, a.element_size(), desc_a)

triton.runtime.driver.active.utils.fill_2d_tma_descriptor(b.data_ptr(), n, k, block_n, block_k, b.element_size(), desc_b)

triton.runtime.driver.active.utils.fill_2d_tma_descriptor(c.data_ptr(), m, n, block_m, block_n, c.element_size(), desc_c)

desc_a = torch.tensor(desc_a, device='cuda')

desc_b = torch.tensor(desc_b, device='cuda')

desc_c = torch.tensor(desc_c, device='cuda')

This is the code that is used to set up the descriptors in the kernel invoke function.

Triton Device Code

Offsets/Pointer Arithmetic:

offs_am = pid_m * block_m

offs_bn = pid_n * block_n

offs_k = 0

Load:

a = tl._experimental_descriptor_load(a_desc_ptr, [offs_am, offs_k], [block_m, block_k], tl.float8e4nv)

b = tl._experimental_descriptor_load(b_desc_ptr, [offs_bn, offs_k], [block_n, block_k], tl.float8e4nv)

Store:

tl._experimental_descriptor_store(c_desc_ptr, accumulator, [offs_am, offs_bn])

We no longer need to calculate a pointer array for both load and store functions in the kernel. Instead, we pass a single descriptor pointer, the offsets, block size and the input datatype. This simplifies address calculation and reduces register pressure, as we no longer have to do complex pointer arithmetic in software and dedicate CUDA cores for address computation.

TMA Performance Analysis

Below, we discuss the PTX instructions for different load mechanisms on Hopper.

PTX for Loading Tile (cp.async) – H100 no TMA

add.s32 %r27, %r100, %r8;

add.s32 %r29, %r100, %r9;

selp.b32 %r30, %r102, 0, %p18;

@%p1 cp.async.cg.shared.global [ %r27 + 0 ], [ %rd20 + 0 ], 0x10, %r30;

@%p1 cp.async.cg.shared.global [ %r29 + 0 ], [ %rd21 + 0 ], 0x10, %r30;

cp.async.commit_group ;

Here, we observe the older cp.async instruction responsible for global memory copies. From the traces below we can see that both loads bypass the L1 cache. A major difference in the newer TMA load is that before tiles from A and B were ready to be consumed by the Tensor Core we would need to execute an ldmatrix instruction that operated on data contained in register files. On Hopper, the data can now be directly reused from shared memory.

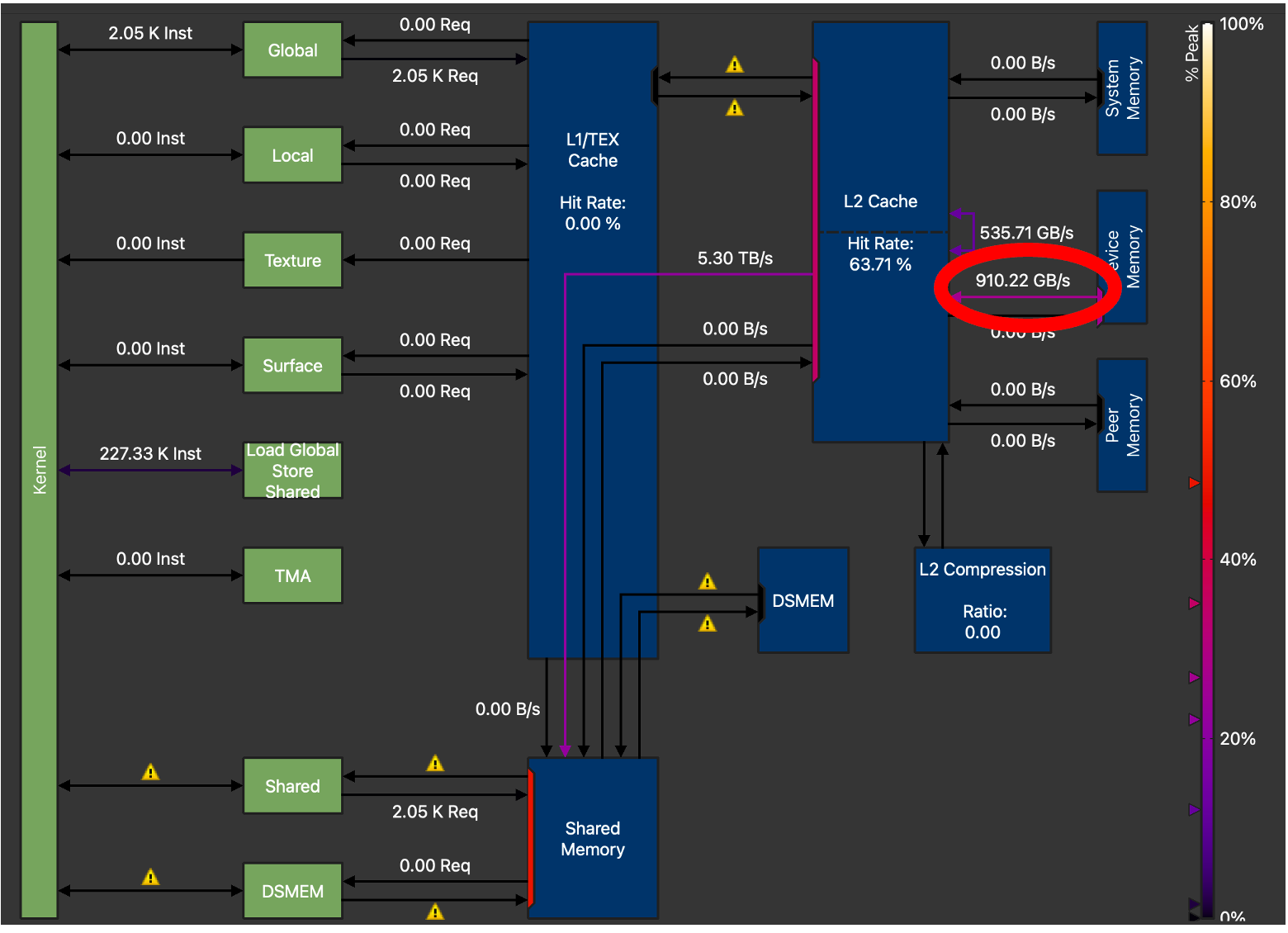

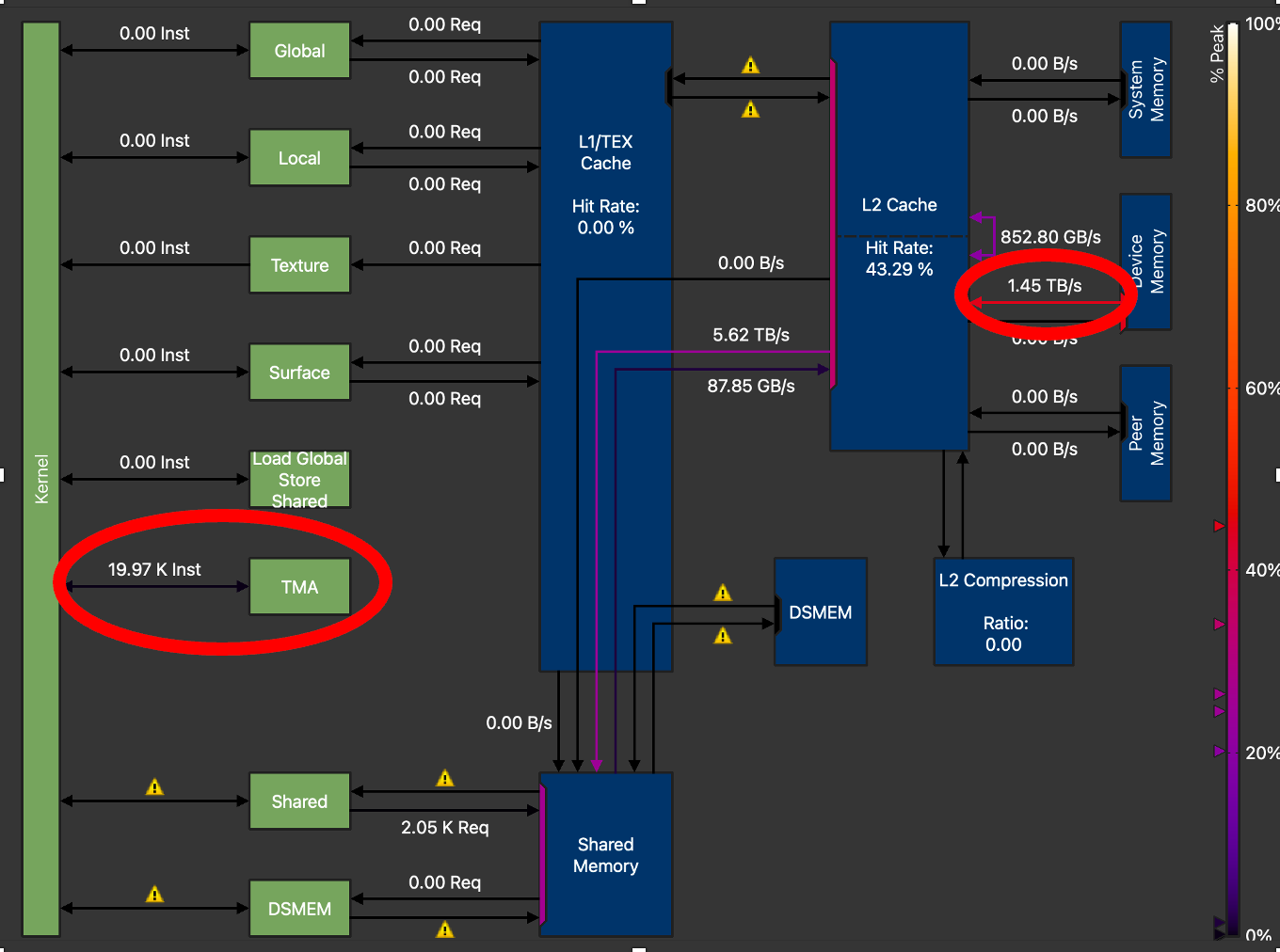

Figure 5. H100 Memory Chart showing GMEM Throughput = 910.22 GB/s (Triton GEMM without TMA) for M=128, N=4096, K=4096

By leveraging TMA through the Triton API changes we mentioned above, we can investigate the PTX that Triton generates for a single 2D tile load with TMA.

PTX for Loading Tile (cp.async.bulk.tensor) – H100 using TMA

bar.sync 0;

shr.u32 %r5, %r4, 5;

shfl.sync.idx.b32 %r66, %r5, 0, 31, -1;

elect.sync _|%p7, 0xffffffff;

add.s32 %r24, %r65, %r67;

shl.b32 %r25, %r66, 7;

@%p8

cp.async.bulk.tensor.2d.shared::cluster.global.mbarrier::complete_tx::bytes [%r24], [%rd26, {%r25,%r152}], [%r19];

The cp.async.bulk.tensor.2d.shared TMA instruction is passed the destination address in shared memory, a pointer to the tensor map, the tensor map coordinates and a pointer to the mbarrier object, respectively.

Figure 6. H100 Memory Chart GMEM Throughput =1.45 TB/s (Triton GEMM with TMA) for M=128, N=4096, K=4096

For optimal performance we tuned the TMA GEMM kernel extensively. Amongst other parameters such as tile sizes, number of warps and number of pipeline stages, the biggest increase in memory throughput was observed when we increased the TMA_SIZE (descriptor size) from 128 to 512. From the above NCU profiles, we can see that the final tuned kernel has increased global memory transfer throughput from 910 GB/s to 1.45 TB/s, a 59% increase in GMEM throughput, over the non-TMA Triton GEMM kernel.

Comparison of CUTLASS and Triton FP8 GEMM and TMA Implementation – Kernel Architecture

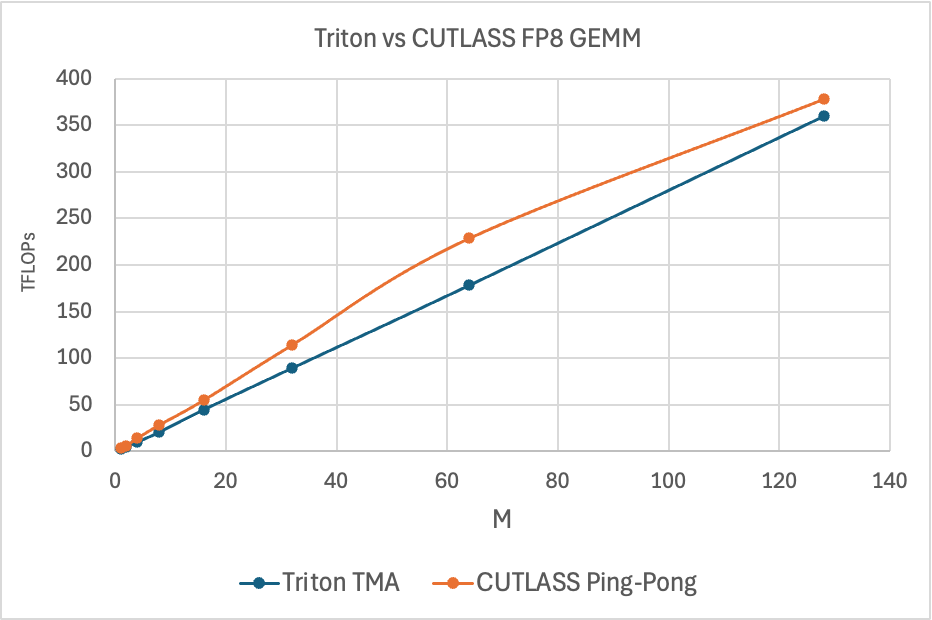

Figure 7. Triton vs CUTLASS Ping-Pong FP8 GEMM TFLOPs, M=M, N=4096, K=4096

The above chart shows the performance of a CUTLASS Ping-Pong GEMM kernel against Triton. The Ping-Pong kernel leverages TMA differently than Triton. It makes use of all of its HW and SW software capabilities, while Triton currently does not. Specifically, CUTLASS supports the below TMA features that help explain the performance gaps in pure GEMM performance:.

- TMA Multicast

- Enables copy of data from GMEM to multiple SMs

- Warp Specialization

- Enables warp groups within a threadblock to take on different roles

- Tensor Map (TMA Descriptor) Prefetch

- Enables prefetching the Tensor Map object from GMEM, which allows pipelining of TMA loads

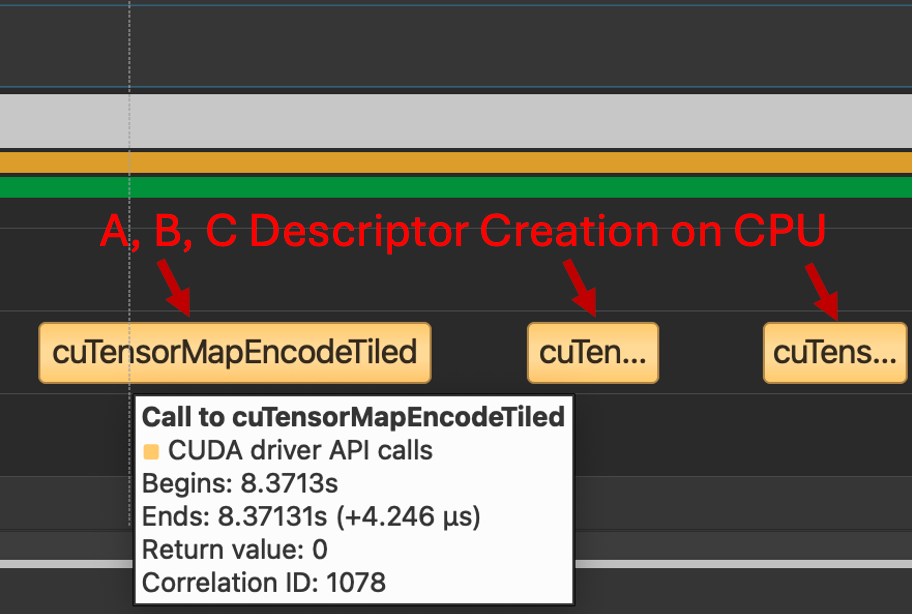

To put the performance numbers in perspective, below we show a ‘speed-up’ chart highlighting the latency differences on a percentage basis:

Figure 8: % Speedup of CUTLASS Ping-Pong vs Triton FP8 with TMA.

This speedup is purely kernel throughput, not including E2E launch overhead which we will discuss below.

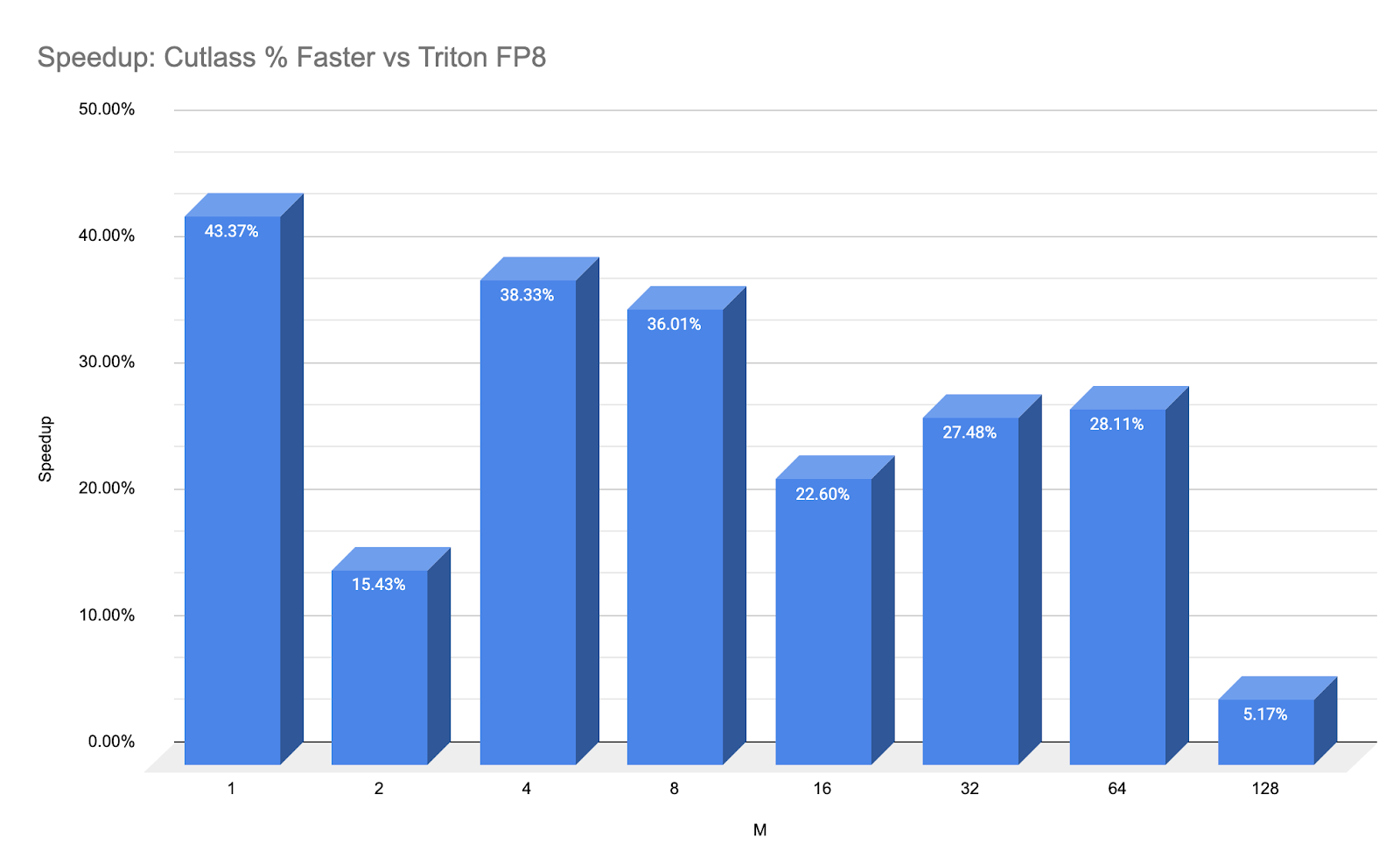

TMA Descriptor movement – a key difference between Triton and CUTLASS with E2E performance implications

As noted previously, creation of a 2D+ dimensional TMA descriptor takes place on the host and is then transferred to the device. However, this transfer process takes place very differently depending on the implementation.

Here we showcase the differences between how Triton transfers TMA descriptors compared with CUTLASS.

Recall, TMA transfers require a special data structure, a tensor map to be created on CPU through the cuTensorMap API, which for an FP8 GEMM Kernel means creating three descriptors, one for each A, B and C. We see below that for both the Triton and CUTLASS Kernels the same CPU procedures are invoked.

Figure 7. Calls to cuTensorMapEncodeTiled (Both Triton and CUTLASS use this path)

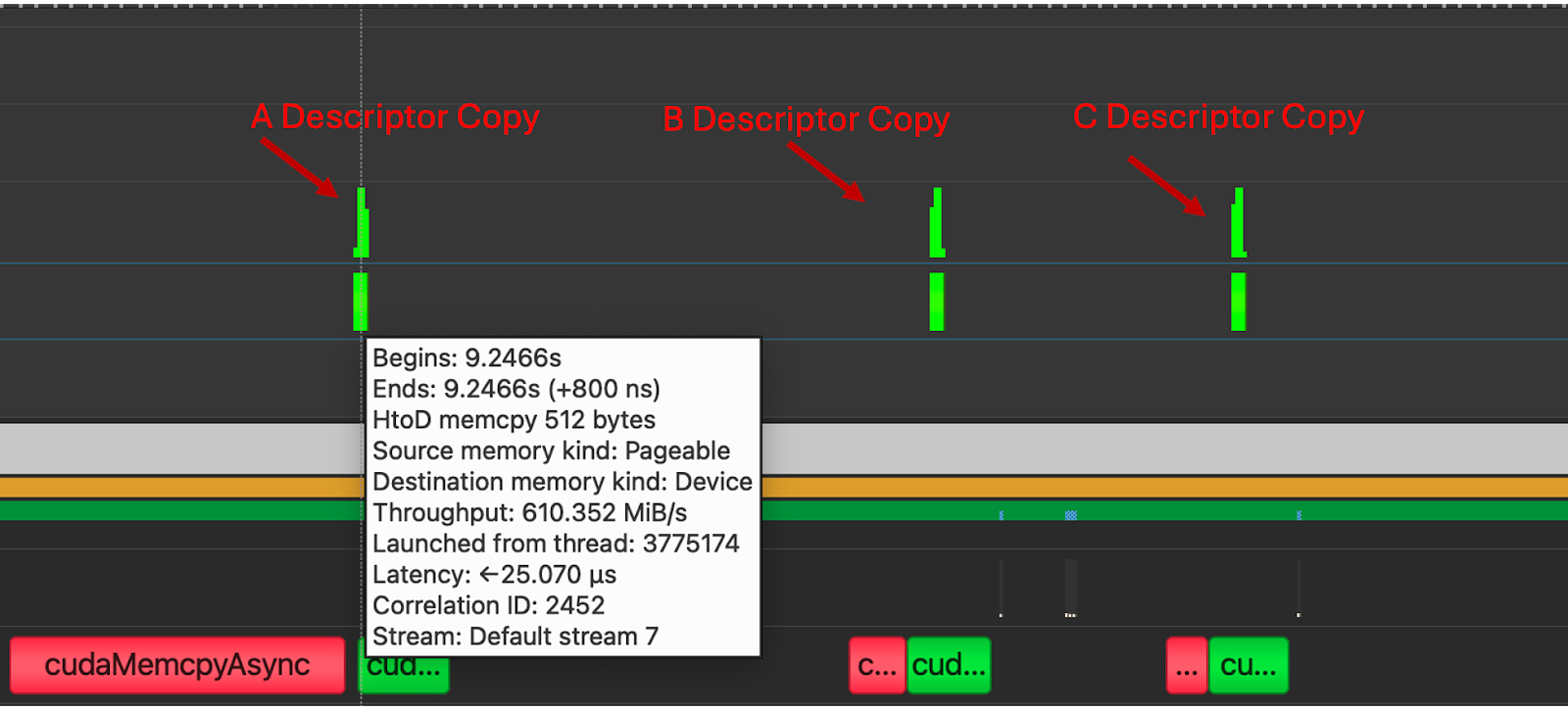

However, for Triton, each descriptor is transferred in its own distinct copy kernel, which adds a significant amount of overhead and serves as a barrier to use this kernel in an end-to-end use inference scenario.

Figure 8. Three H2D Copy Kernels are launched before the kernel execution, for A, B and C

These copies are not observed in the CUTLASS implementation, due to the way that TMA descriptors are passed to the kernel. We can see from the PTX below that with Cutlass, tensor maps are passed-by-value to the kernel.

.entry _ZN7cutlass13device_kernelIN49_GLOBAL__N__8bf0e19b_16_scaled_mm_c3x_cu_2bec3df915cutlass_3x_gemmIaNS_6half_tENS1_14ScaledEpilogueEN4cute5tupleIJNS5_1CILi64EEENS7_ILi128EEES9_EEENS6_IJNS7_ILi2EEENS7_ILi1EEESC_EEENS_4gemm32KernelTmaWarpSpecializedPingpongENS_8epilogue18TmaWarpSpecializedEE10GemmKernelEEEvNT_6ParamsE(

.param .align 64 .b8 _ZN7cutlass13device_kernelIN49_GLOBAL__N__8bf0e19b_16_scaled_mm_c3x_cu_2bec3df915cutlass_3x_gemmIaNS_6half_tENS1_14ScaledEpilogueEN4cute5tupleIJNS5_1CILi64EEENS7_ILi128EEES9_EEENS6_IJNS7_ILi2EEENS7_ILi1EEESC_EEENS_4gemm32KernelTmaWarpSpecializedPingpongENS_8epilogue18TmaWarpSpecializedEE10GemmKernelEEEvNT_6ParamsE_param_0[1024]

mov.b64 %rd110, _ZN7cutlass13device_kernelIN49_GLOBAL__N__8bf0e19b_16_scaled_mm_c3x_cu_2bec3df915cutlass_3x_gemmIaNS_10bfloat16_tENS1_14ScaledEpilogueEN4cute5tupleIJNS5_1CILi64EEES8_NS7_ILi256EEEEEENS6_IJNS7_ILi1EEESB_SB_EEENS_4gemm24KernelTmaWarpSpecializedENS_8epilogue18TmaWarpSpecializedEE10GemmKernelEEEvNT_6ParamsE_param_0;

add.s64 %rd70, %rd110, 704;

cvta.param.u64 %rd69, %rd70;

cp.async.bulk.tensor.2d.global.shared::cta.bulk_group [%rd69, {%r284, %r283}], [%r1880];

Figure 9. CUTLASS kernel PTX showing pass-by-value

By directly passing the TMA Descriptor as opposed to passing a global memory pointer, the CUTLASS kernel avoids the three extra H2D copy kernels and instead these copies are included in the single device kernel launch for the GEMM.

Because of the difference in how descriptors are moved to the device, the kernel latencies including the time to prepare the tensors to be consumed by the TMA is drastically different. For M=1-128, N=4096, K=4096 the CUTLASS pingpong kernel has an average latency of 10us Triton TMA kernels complete in an average of 4ms. This is a factor of ~3330x slower and appears to be directly linked to the 3 independent kernel launches for TMA descriptor transfer by Triton.

Cuda graphs may be one way to reduce this, but given the overhead created by the H2D copies the current Triton implementation when measured end to end is not competitive. A rework of how the Triton compiler manages TMA descriptors would likely resolve this gap. We thus focused on comparing the actual compute kernel throughput and not E2E in our data above.

Results Summary

Figure 10. Triton FP8 TMA GEMM TFLOPs Comparison

| M | Triton TMA | Triton Tutorial | Triton SplitK | cuBLAS FP8 | cuBLAS FP16 | CUTLASS Ping-Pong FP8 |

| 1 | 2.5 | 1 | 2.4 | 1.5 | 1.8 | 3.57 |

| 2 | 5.1 | 2.5 | 4.8 | 3.1 | 3.6 | 5.9 |

| 4 | 10.3 | 7.21 | 9.6 | 6.1 | 7.2 | 14.3 |

| 8 | 21.0 | 16.5 | 19.2 | 12.3 | 14.4 | 28.6 |

| 16 | 44.5 | 41.0 | 37.2 | 24.5 | 27.7 | 55.1 |

| 32 | 89.7 | 81.2 | 72.2 | 71.6 | 56.8 | 114.4 |

| 64 | 178.5 | 163.7 | 130.8 | 144.6 | 105.3 | 228.7 |

| 128 | 359.7 | 225.9 | 160.1 | 244.0 | 189.2 | 377.7 |

Figure 11. Triton FP8 TMA GEMM TFLOPs Comparison Table

The above chart and table summarize the gain we’ve been able to achieve on a single NVIDIA H100 for FP8 GEMM, by leveraging the TMA Hardware Unit, over non-TMA Triton kernels and high performance CUDA (cuBLAS) kernels. The key point to note is this kernel’s superior scaling (with the batch size) properties over the competition. The problem sizes we benchmarked on are representative of the matrix shapes found in small-to-medium batch size LLM inference. Thus, TMA GEMM kernel performance in the mid-M regime (M=32 to M=128) will be critical for those interested in leveraging this kernel for FP8 LLM deployment use cases, as the FP8 compressed data type can allow larger matrices to fit in GPUs memory.

To summarize our analysis, the TMA implementation in Triton and CUTLASS differ in terms of full featureset support (multicast, prefetch etc.) and how the TMA Descriptor is passed to the GPU kernel. If this descriptor is passed in a manner that more closely matches the CUTLASS kernel (pass-by-value), the extraneous H2D copies could be avoided and thus the E2E performance would be greatly improved.

Future Work

For future research, we plan to improve upon these results, by working with the community to incorporate the CUTLASS architecture of TMA loads into Triton as well as investigating the Cooperative Kernel for FP8 GEMM, a modified strategy to the Ping-Pong Kernel.

In addition, once features like thread block clusters and TMA atomic operations are enabled in Triton, we may be able to get further speedups by leveraging the SplitK strategy in the TMA GEMM Kernel, as atomic operations on Hopper can be performed in Distributed Shared Memory (DSMEM) as opposed to L2 Cache. We also note the similarities of NVIDIA Hopper GPUs with other AI hardware accelerators like Google’s TPU and IBM’s AIU which are dataflow architectures. On Hopper, data can now “flow” from GMEM to a network of connected SMs due to the additions of TMA, which we discussed extensively in this blog, and DSMEM, which we plan to cover in a future post.