As training jobs become larger, the likelihood of failures such as preemptions, crashes, or infrastructure instability rises. This can lead to significant inefficiencies in training and delays in time-to-market. At these large scales, efficient distributed checkpointing is crucial to mitigate the negative impact of failures and to optimize overall training efficiency (training goodput).

Training badput is the percent of the job’s overall duration where training is not progressing. We can calculate training badput using the mean time between interruptions (MTBI) rather than the overall duration so that the derivation is applicable to any training duration. For calculating checkpointing badput as a percent, we take the amount of time lost from training due to checkpointing within the MTBI interval and divide this by MTBI to determine checkpointing badput as a percent. Let’s formalize checkpoint badput and the contributing factors:

Figure 1: Formal definition of Checkpointing Badput

The formulation above decomposes into three components:

- Loading: time to load checkpoint from storage when recovering from interruption

- Saving Overhead: overhead on training from saving checkpoints

- Computation Loss: computation time lost when resuming from the most recent checkpoint

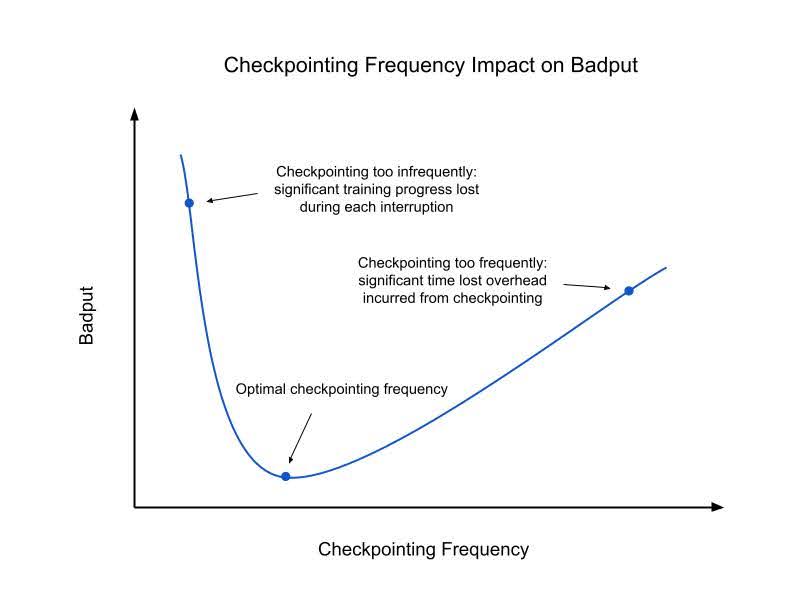

Recent features, including process based async checkpointing, save plan caching and rank local checkpointing etc. added by PyTorch DistributedCheckpoint (DCP) improve the checkpointing saving overhead and subsequently the checkpoint saving time. Further minimizations to checkpoint badput then become dependent on the checkpoint interval. Checkpointing infrequently leads to larger gaps between checkpoints, increasing the amount of training progress that can be lost when having to revert to a previous checkpoint. However, since checkpointing introduces saving overhead, saving checkpoints too frequently can significantly disrupt training performance. Determining the optimal frequency can be determined numerically, please take a look at the appendix for the exact formulation. Below is an intuitive understanding of checkpointing frequency and its impact on training badput.

Figure 2: Checkpointing Frequency Impact on Badput

Historically, training workloads rely on persistent storage (ex: NFS, Lustre GCS) for writing and reading checkpoints. At large scales there is additional latency introduced when dealing with persistent storage, which unfortunately limits the rate at which checkpoints can be saved. Google and PyTorch recently collaborated on a local checkpointing solution using DCP, enabling frequent saves to local storage. As we will show later, local checkpointing overcomes the limitations of traditional setups and enhances training goodput.

Minimizing Saving Overhead

In typical checkpointing workflows, GPUs are idle while checkpoint data transfers from GPU to CPU and then to storage, with training only resuming once data is saved. Asynchronous checkpointing significantly reduces GPU blocking time by offloading the data saving process to CPU threads. Only the GPU offloading step remains synchronous. This allows GPU-based training to continue concurrently while checkpoint data uploads to storage. It is primarily used for intermediate or fault-tolerant checkpoints, as it frees GPUs much faster than synchronous methods. Training resumes immediately, greatly improving training goodput over synchronous checkpointing. For more details, refer to this post.

GPU utilization drop from GIL contention

The Global Interpreter Lock (GIL) in Python is a mechanism that prevents multiple native threads from executing Python bytecode at the same time. This lock is necessary mainly because CPython’s memory management is not thread-safe.

DCP’s current use of background threads for metadata collectives and uploading to storage, despite being asynchronous, creates contention for the GIL with trainer threads. This significantly impacts GPU utilization and increases end-to-end upload latency. For large-scale checkpoints, the overhead of the CPU parallel processing has a suppressive effect on net GPU training speed since CPUs also drive the training process via GPU kernel launches.

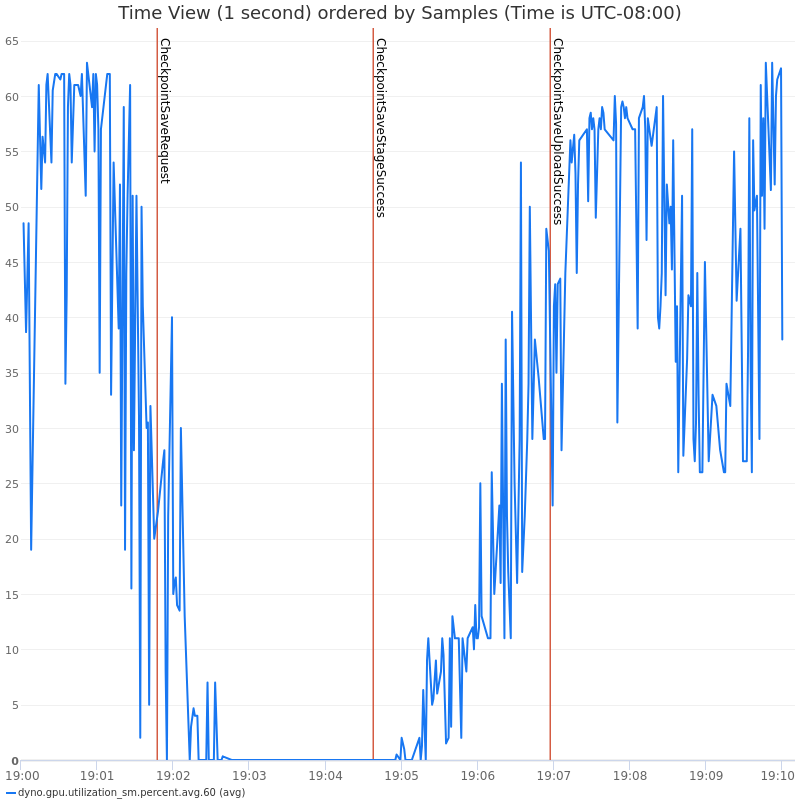

Please refer to the following figure from our experiments, demonstrating the impact of thread-based asynchronous checkpointing on GPU utilization and training QPS.

Here is a more detailed view of the GIL contention causes a slow checkpoint save and lower training QPS:

Figure 3 & 4: Impact of Asynchronous Checkpointing using Threads on GPU utilization & Training QPS

Checkpoint Staging Cost

During asynchronous checkpointing, GPU memory is offloaded to CPU memory in a step known as staging. This introduces overheads related to memory allocation and deallocation, including memory fragmentation, page faults and memory synchronization. By addressing these overheads, the overall blocking time spent on checkpointing can be reduced, improving overall training goodput.

Figure 5: Overview of Staging Step

Collective communications cost

DCP performs multiple collectives today for various reasons: deduplication, global metadata for the checkpoint, resharding, and distributed exception handling. Collectives are costly as these require network I/O and pickling/unpickling of large python objects being sent across the GPU network. As job scale increases, these collectives become exceedingly costly, resulting in significantly higher end-to-end latency and the potential for collective timeouts.

Cache the Plans

For fault tolerance, multiple checkpoints are taken during a job. DCP clearly separates the planning and storage I/O stages. In most cases, only the state dict changes between checkpoint save attempts, while the plan remains consistent. This allows for plan caching, incurring the cost only on the first save and amortizing it across subsequent attempts. This significantly reduces the overall overhead, as only updated plans are sent over the collective during synchronization.

Cache the Metadata

Generating global metadata for checkpointing is costly due to the collective overhead. To mitigate this, checkpoint metadata can be cached alongside save plans across multiple save attempts, provided the plans remain unchanged.

Process based checkpointing

DCP currently uses background threads for metadata collectives and upload to storage. Although these expensive steps are done asynchronously, it leads to contention for GIL with the trainer threads. This causes the GPU utilization (QPS) to suffer significantly and also increases the e2e upload latency quite a bit. Figure 6 below illustrates how process-based async checkpointing effectively reduces GIL contention with trainers. This stands in contrast to Figures 3 & 4, where thread-based async checkpointing is shown to slow down training due to GIL contention.

Figure 6: GIL Contention Resolved when using Process-Based Asynchronous Checkpointing

Pinned memory staging

Our internal experimentations have concluded that staging our tensors to CPU or shared memory can be sped up by utilizing the pinned shared memory tensors, which has the potential to significantly improve async checkpointing blocking time. One can read here and here to know more about this strategy.

The basic idea is that due to certain mechanics of GPUs, the data transfer to pageable memory often happens via pinned (non-pageable) memory by default, and this can be optimized by designating certain byte address ranges as pinned, allowing direct copying from GPU to shared memory. With this approach, we see 2x improvement in staging time (GPU blocking time), significantly helping training goodput and allowing more aggressive checkpoint intervals.

Figure 7: Demonstrates Pinned Memory Staging

In Cluster Local Checkpointing

Local checkpointing refers to saving and loading checkpoints using local storage, meaning that each node will save and load from its local storage (SSD, RAMDisk, etc) rather than a global persistent storage. The advantages of local checkpointing are straightforward, yet best utilizing them can be difficult due to the complexities of remediation in large-scale training jobs.

Within a training job, interruptions typically occur at the level of individual nodes. Nodes can fail for various reasons, potentially making their local state inaccessible to the rest of the workload. For quick recoveries, training jobs will often have reserved spare capacity that can be used as replacements. As such, the set of nodes actively training is dynamic. A shift in this active set necessitates an adjustment to the optimized network topology, which may further influence the state each node needs to train. Unlike with persistent storage where training state is always available, when relying on local storage, changes in the set of active nodes result in a subset of nodes that are missing the needed training state.

To guard against these cases, workloads will often rely on some form of state replication and backups to persistent storage. While it is important to always maintain some cadence of saving backups to persistent storage, the advantages introduced with local checkpointing motivate sophisticated solutions that can handle state replication.

State can either be replicated through enabling data parallelism or during checkpoint saving, in which each node’s state is shared with another node as a backup. Replicating state when saving introduces additional latency as each node will need to save its own state and the state of another node. During checkpoint loading when, both approaches require functionality to transfer state between nodes and logic to understand which transfers need to take place.

Google, in collaboration with PyTorch, recently released a DCP-based local checkpointing solution. The current solution takes advantage of data parallelism and handles replication logic during loading. Future work will also enable replication during saving. This local checkpointing solution can be found in Google Cloud’s Resiliency library and is incorporated into several goodput-optimized training recipes.

Impact of checkpointing optimizations on goodput

Let’s put all of these optimizations back into perspective of training goodput using the formula for checkpoint badput. To calculate badput, we measured overhead incurred from checkpointing, total time to save a checkpoint, and time to load checkpoints. The results below were obtained on 54 Google Cloud A3Ultra VMs (432 NVIDIA H200 SXM GPUs) using Llama 3 405B.

| Baseline asynchronous checkpointing with GCS as persistent storage | Previous column + DCP plan + metadata caching | Previous column + dedicated process based checkpointing + pinned memory | Previous column + local checkpointing | |

| Checkpointing overhead (excluding first checkpoint) | 18.5s | 5.5s | 1.5s | 2.3s |

| Total time to save checkpoint (excluding first checkpoint) | ~126s | ~135s | ~135s | ~47s |

| Time to load checkpoints | 94s | 94s | 94s | 80s |

The results highlight that the DCP optimizations significantly minimize checkpointing overhead to near-zero. As expected, local checkpointing significantly cuts down on the time to save and load checkpoints. The checkpoint overhead is slightly higher when using local checkpointing due to the decision to exclude checkpoint deduplication logic. This results in each node writing larger files to storage. Future work aims to reduce checkpoint file size when using local checkpointing.

With the measurements in the table above, we can determine the optimal checkpointing frequency via the derivation in the Appendix and calculate the total badput caused by checkpointing.

Figure 8: Checkpointing Impact on Badput

The plot shows that as interruptions become more frequent, the impact each checkpointing optimization has on training goodput becomes more significant. In the most extreme cases where failures occur hourly, these checkpointing optimizations can reduce badput by 9 percentage points.

These results highlight that optimized checkpointing solutions are essential for large-scale training jobs that deal with frequent interruptions.

How to enable the optimizations in DCP?

These features are already available as part of the PyTorch nightly builds, and you can test out PyTorch’s Asynchronous DCP checkpointing directly in TorchTitan. The following are instructions to enable these features:

- Process-based asynchronous checkpointing:

- Set the async_checkpointer_type to AsyncCheckpointerType.PROCESS in the async_save API. (file: pytorch/torch/distributed/checkpoint/state_dict_saver.py)

- Save plan caching:

- Set the enable_plan_caching flag to true in the DefaultSavePlanner. (file: pytorch/torch/distributed/checkpoint/default_planner.py)

- Enable pinned memory-based staging

- Create a stager with use_pinned_memory flag set to true in the StagingOptions. (file: https://github.com/pytorch/pytorch/blob/main/torch/distributed/checkpoint/staging.py)

- In cluster local checkpointing: https://github.com/AI-Hypercomputer/resiliency

Appendix

Taking the formula for checkpointing badput, the optimal checkpoint interval can be derived as follows:

where is defined as