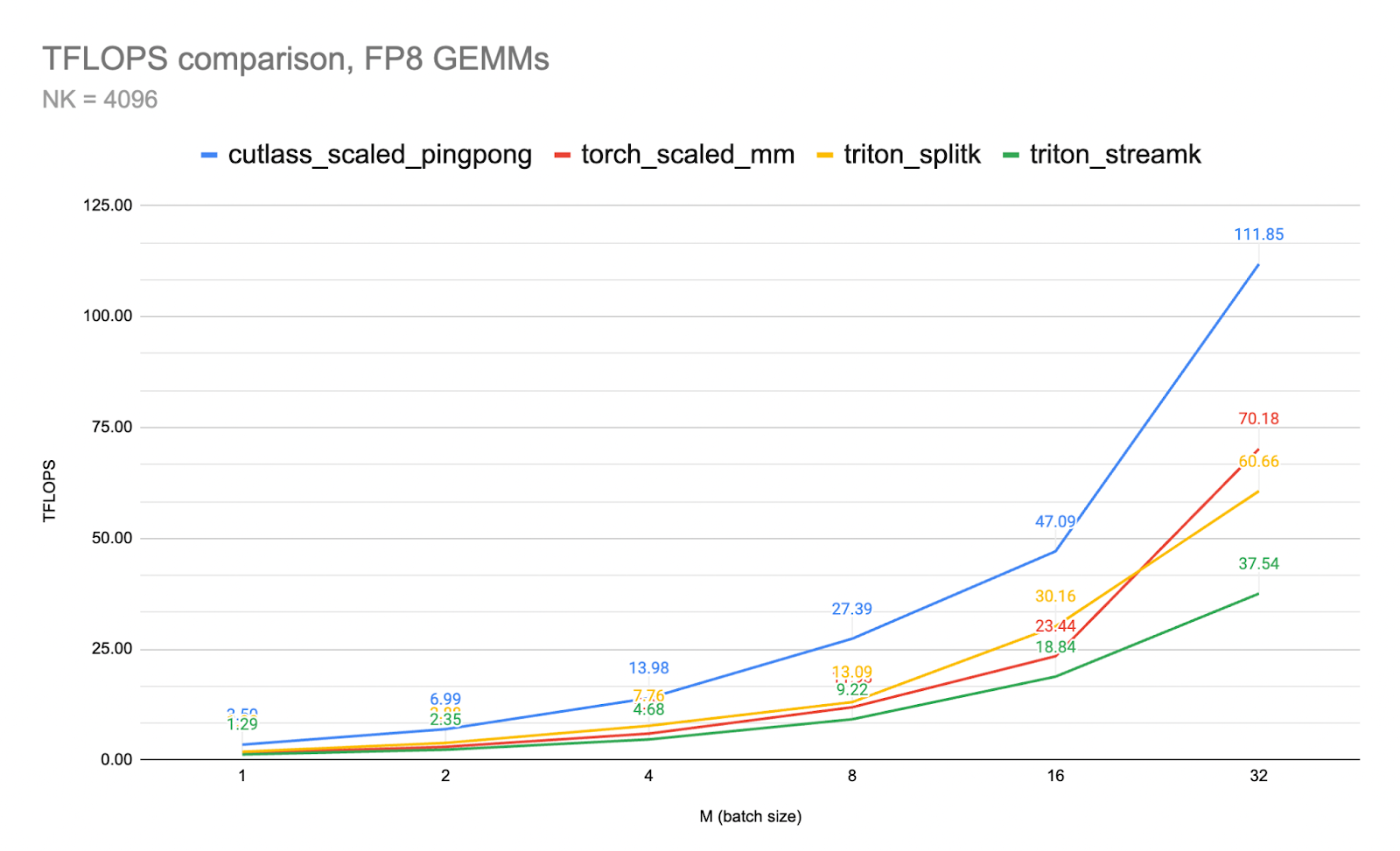

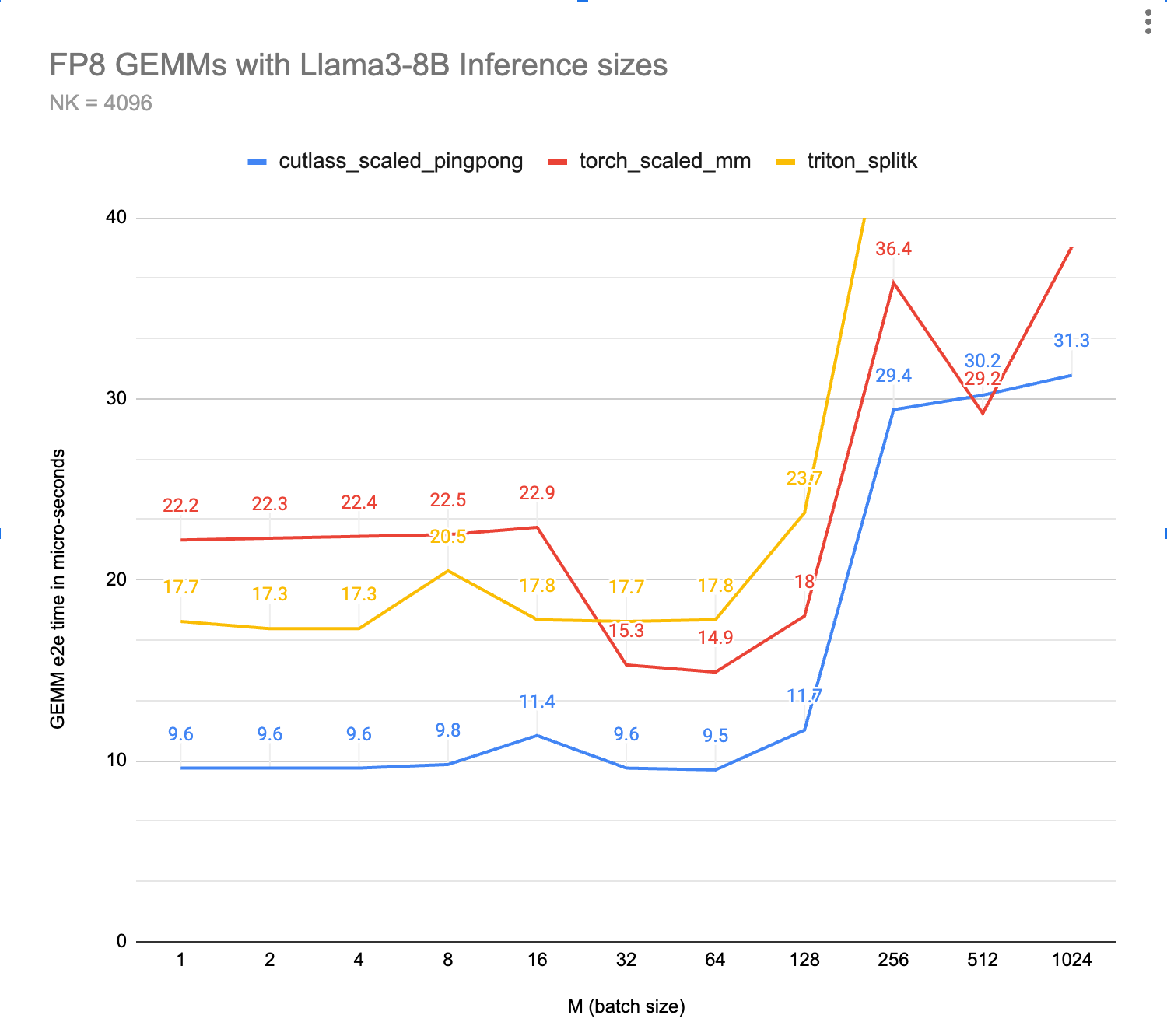

Figure 1. FP8 GEMM Throughput Comparison CUTLASS vs Triton

Summary

In this post, we provide an overview, with relevant FP8 inference kernel benchmarking, of the CUTLASS Ping-Pong GEMM kernel.

Ping-Pong is one of the fastest matmul (GEMM) kernel architectures available for the Hopper GPU architecture. Ping-Pong is a member of the Warp Group Specialized Persistent Kernels family, which includes both Cooperative and Ping-Pong variants. Relative to previous GPUs, Hopper’s substantial tensor core compute capability requires deep asynchronous software pipelining in order to achieve peak performance.

The Ping-Pong and Cooperative kernels exemplify this paradigm, as the key design patterns are persistent kernels to amortize launch and prologue overhead, and ‘async everything’ with specialized warp groups with two consumers and one producer, to create a highly overlapped processing pipeline that is able to continuously supply data to the tensor cores.

When the H100 (Hopper) GPU was launched, Nvidia billed it as the first truly asynchronous GPU. That statement highlights the need for H100 specific kernel architectures to also be asynchronous in order to fully maximize computational/GEMM throughput.

The pingpong GEMM, introduced in CUTLASS 3.x, exemplifies this by moving all aspects of the kernel to a ‘fully asynchronous’ processing paradigm. In this blog, we’ll showcase the core features of the ping-pong kernel design as well as showcase its performance on inference workloads vs cublas and triton split-k kernels.

Ping-Pong Kernel Design

Ping-Pong (or technically ‘sm90_gemm_tma_warpspecialized_pingpong’) operates with an asynchronous pipeline, leveraging warp specialization. Instead of the more classical homogeneous kernels, “warp groups” take on specialized roles. Note that a warp group consists of 4 warps of 32 threads each, or 128 total threads.

On earlier architectures, latency was usually hidden by running multiple thread blocks per SM. However, with Hopper, the Tensor Core throughput is so high that it necessitates moving to deeper pipelines. These deeper pipelines then hinder running multiple thread blocks per SM. Thus, persistent thread blocks now issue collective main loops across multiple tiles and multiple warp groups. Thread block clusters are allocated based on the total SM count.

For Ping-Pong, each warp group takes on a specialized role of either Data producer or Data consumer.

The producer warp group focuses on producing data movement to fill the shared memory buffers (via TMA). Two other warp groups are dedicated consumers that process the math (MMA) portion with tensor cores, and then do any follow up work and write their results back to global memory (epilogue).

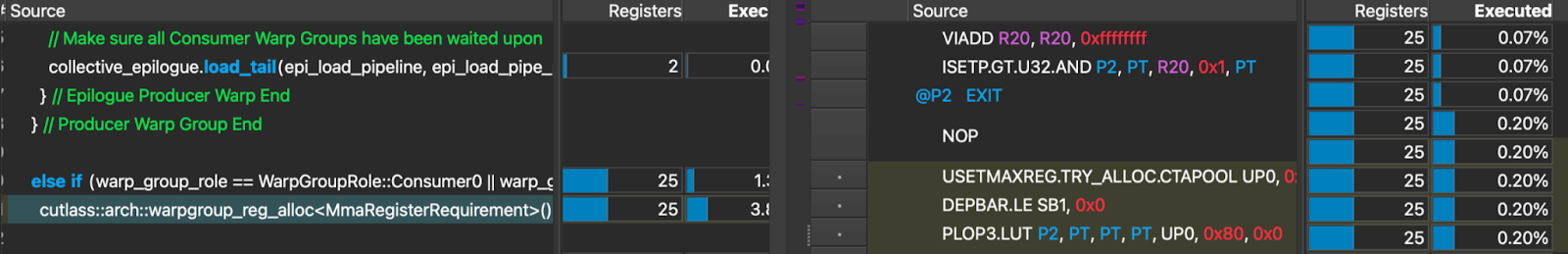

Producer warp groups work with TMA (Tensor Memory Accelerator), and are deliberately kept as lightweight as possible. In fact, in Ping-Pong, they deliberately reduce their register resources to improve occupancy. Producers will reduce their max register counts by 40, vs consumers will increase their max register count by 232, an effect we can see in the CUTLASS source and corresponding SASS:

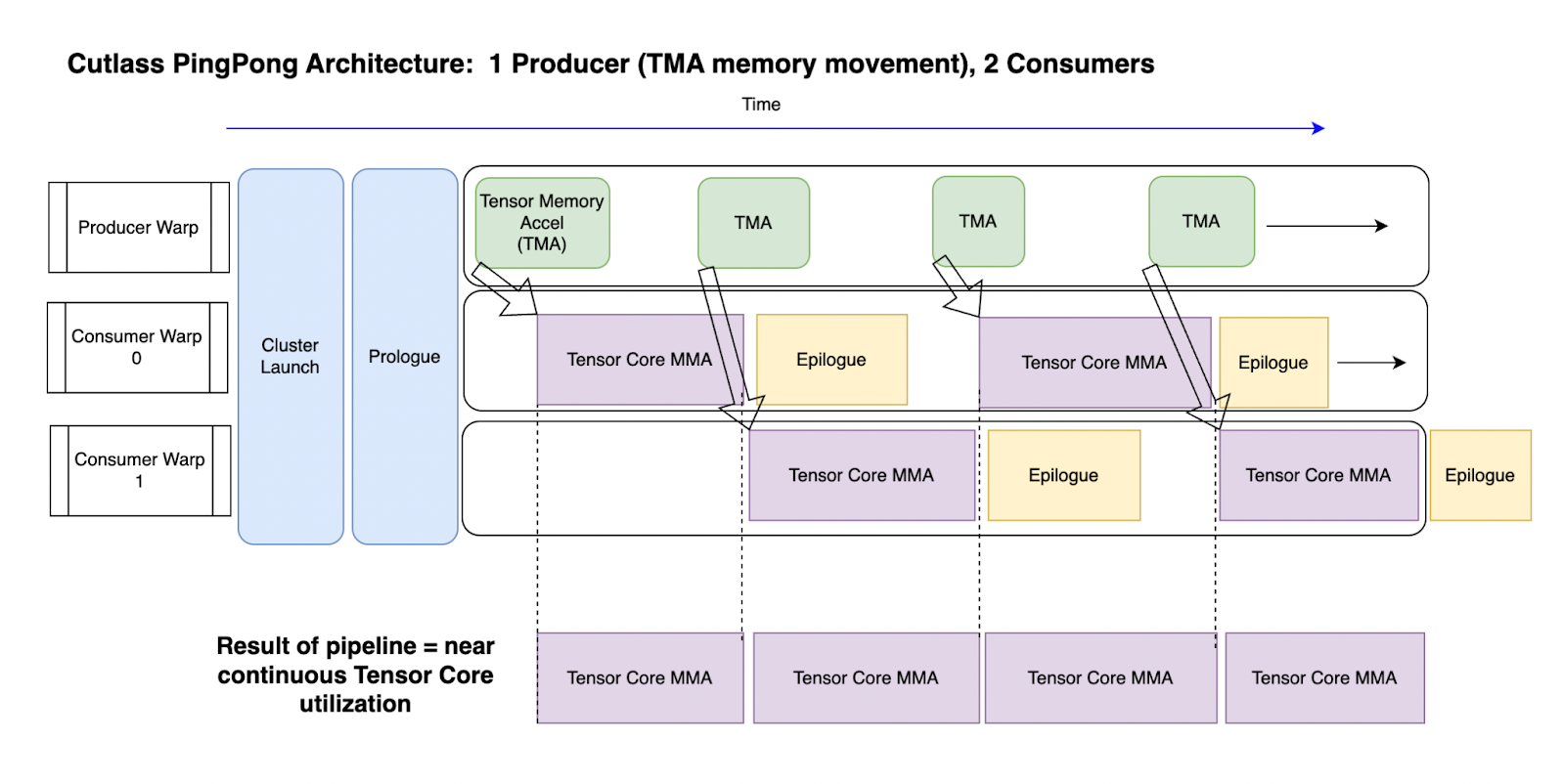

Unique to Ping-Pong, each consumer works on separate C output tiles. (For reference, the cooperative kernel is largely equivalent to Ping-Pong, but both consumer groups work on the same C output tile). Further, the two consumer warp groups then split their work between the main loop MMA and epilogue.

This is shown in the below image:

Figure 2: An overview of the Ping-Pong Kernel pipeline. Time moves left to right.

By having two consumers, it means that one can be using the tensor cores for MMA while the other performs the epilogue, and then vice-versa. This maximizes the ‘continuous usage’ of the tensor cores on each SM, and is a key part of the reason for the max throughput. The tensor cores can be continuously fed data to realize their (near) maximum compute capability. (See the bottom section of the Fig 2 illustration above).

Similar to how Producer threads stay focused only on data movements, MMA threads only issue MMA instructions in order to achieve peak issue rate. MMA threads must issue multiple MMA instructions and keep these in flight against TMA wait barriers.

An excerpt of the kernel code is shown below to cement the specialization aspects:

// Two types of warp group 'roles'

enum class WarpGroupRole {

Producer = 0,

Consumer0 = 1,

Consumer1 = 2

};

//warp group role assignment

auto warp_group_role = WarpGroupRole(canonical_warp_group_idx());

Data Movement with Producers and Tensor Memory Accelerator

The producer warps focus exclusively on data movement – specifically they are kept as lightweight as possible and in fact give up some of their register space to the consumer warps (keeping only 40 registers, while consumers will get 232). Their main task is issuing TMA (tensor memory accelerator) commands to move data from Global memory to shared memory as soon as a shared memory buffer is signaled as being empty.

To expand on TMA, or Tensor Memory Accelerator, TMA is a hardware component introduced with H100’s that asynchronously handles the transfer of memory from HBM (global memory) to shared memory. By having a dedicated hardware unit for memory movement, worker threads are freed to engage in other work rather than computing and managing data movement. TMA not only handles the movement of the data itself, but also calculates the required destination memory addresses, can apply any transforms (reductions, etc.) to the data and can handle layout transformations to deliver data to shared memory in a ‘swizzled’ pattern so that it’s ready for use without any bank conflicts. Finally, it can also multicast the same data if needed to other SM’s that are members of the same thread cluster. Once the data has been delivered, TMA will then signal the consumer of interest that the data is ready.

CUTLASS Asynchronous Pipeline Class

This signaling between producers and consumers is coordinated via the new Asynchronous Pipeline Class which CUTLASS describes as follows:

“Implementing a persistent GEMM algorithm calls for managing dozens of different kinds of asynchronously executing operations that synchronize using multiple barriers organized as a circular list.

This complexity is too much for human programmers to manage by hand.

As a result, we have developed [CUTLASS Pipeline Async Class]…”

Barriers and synchronization within the Ping-Pong async pipeline

Producers must ‘acquire’ a given smem buffer via ‘producer_acquire’. At the start, a pipeline is empty meaning that producer threads can immediately acquire the barrier and begin moving data.

PipelineState mainloop_pipe_producer_state = cutlass::make_producer_start_state<MainloopPipeline>();

Once the data movement is complete, producers issue the ‘producer_commit’ method to signal the consumer threads that data is ready.

However, for Ping-Pong, this is actually a noop instruction since TMA based producer’s barriers are automatically updated by the TMA when writes are completed.

consumer_wait – wait for data from producer threads (blocking).

consumer_release – signal waiting producer threads that they are finished consuming data from a given smem buffer. In other words, allow producers to go to work refilling this with new data.

From there, synchronization will begin in earnest where the producers will wait via the blocking producer acquire until they can acquire a lock, at which point their data movement work will repeat. This continues until the work is finished.

To provide a pseudo-code overview:

//producer

While (work_tile_info.is_valid_tile) {

collective_mainloop.dma() // fetch data with TMA

scheduler.advance_to_next_work()

Work_tile_info = scheduler.get_current_work()

}

// Consumer 1, Consumer 2

While (work_tile_info.is_valid_tile()) {

collective_mainloop.mma()

scheduler.advance_to_next_work()

Work_tile_info = scheduler.get_current_work()

}

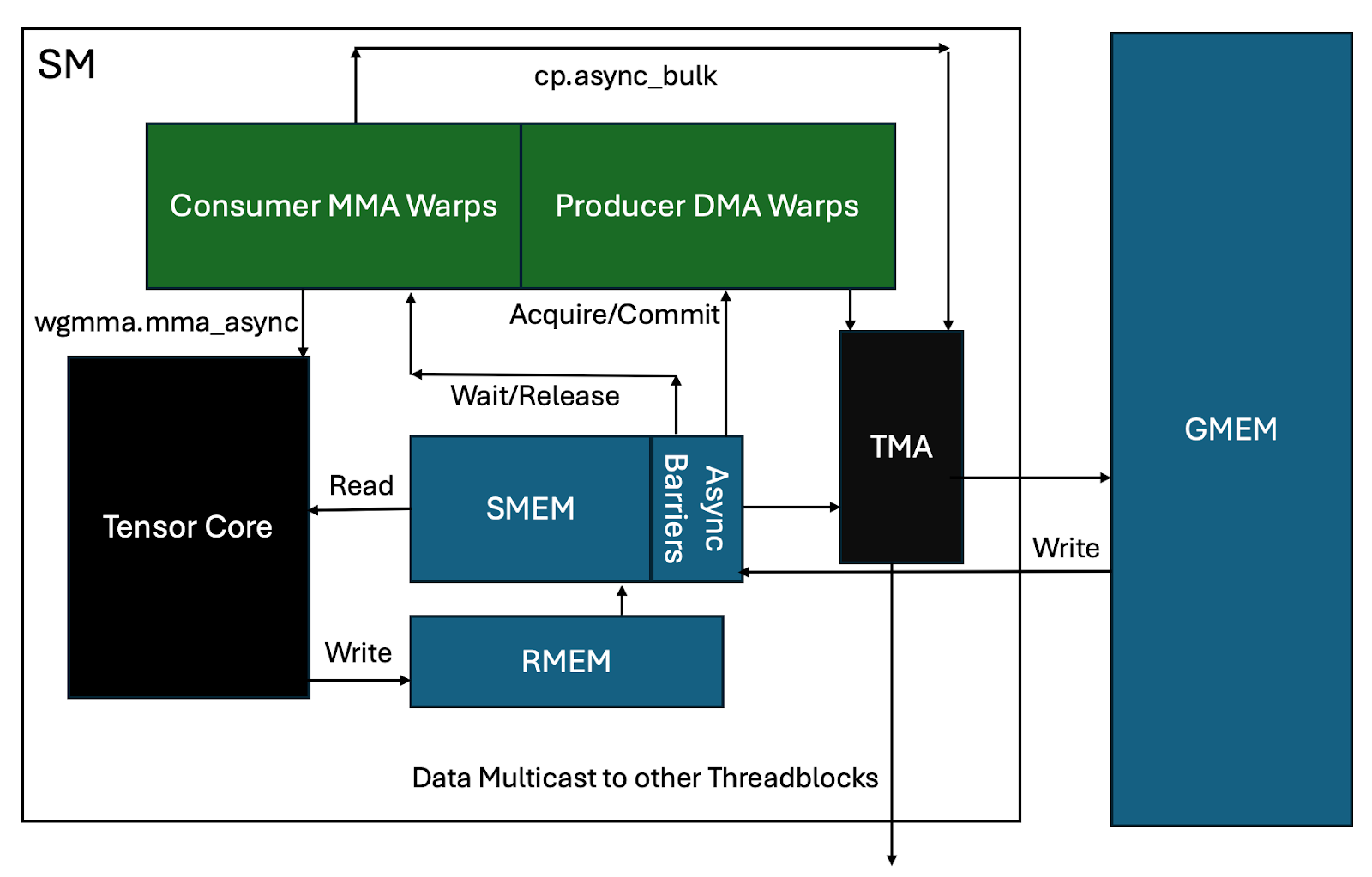

And a visual birds-eye view putting it all together with the underlying hardware:

Figure 3: An overview of the full async pipeline for Ping-Pong

Step-by-Step Breakdown of Ping-Pong Computation Loop

Finally, a more detailed logical breakout of the Ping-Pong processing loop:

A – Producer (DMA) warp group acquires a lock on a shared memory buffer.

B – this allows it to kick off a tma cp_async.bulk request to the tma chip (via a single thread).

C – TMA computes the actual shared memory addressing required, and moves the data to shared memory. As part of this, swizzling is performed in order to layout the data in smem for the fastest (no bank conflict) access.

C1 – potentially, data can also be multicast to other SMs and/or it may need to wait for data from other tma multicast to complete the loading. (threadblock clusters now share shared memory across multiple SMs!)

D – At this point, the barrier is updated to signal the arrival of the data to smem.

E – The relevant consumer warpgroup now gets to work by issuing multiple wgmma.mma_async commands, which then read the data from smem to Tensor cores as part of it’s wgmma.mma_async matmul operation.

F – the MMA accumulator values are written to register memory as the tiles are completed.

G – the consumer warp group releases the barrier on the shared memory.

H – the producer warp groups go to work issuing the next tma instruction to refill the now free smem buffer.

I – The consumer warp group simultaneously applies any epilogue actions to the accumulator, and then move data from register to a different smem buffer.

J – The consumer warp issues a cp_async command to move data from smem to global memory.

The cycle repeats until the work is completed. Hopefully this provides you with a working understanding of the core concepts that power Ping-Pong’s impressive performance.

Microbenchmarks

To showcase some of Ping-Pong’s performance, below are some comparison charts related to our work on designing fast inference kernels.

First a general benchmarking of the three fastest kernels so far (lower is better): \

Figure 4, above: Benchmark timings of FP8 GEMMs, lower is better (faster)

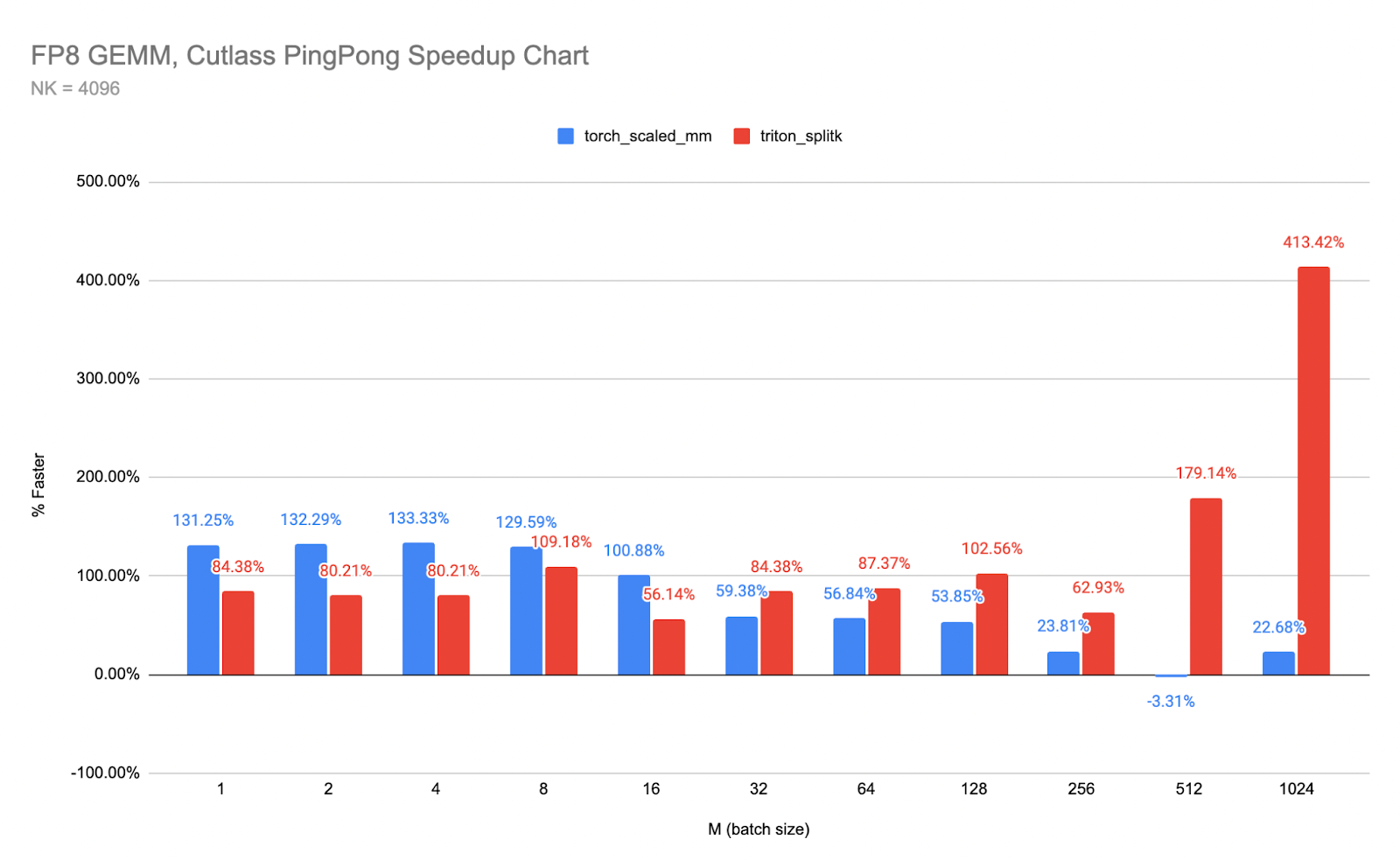

And translating that into a relative speedup chart of Ping-Pong vs cuBLAS and Triton:

Figure 5, above: Relative speedup of Ping-Pong vs the two closest kernels.

The full source code for the Ping-Pong kernel is here (619 lines of deeply templated CUTLASS code, or to paraphrase the famous turtle meme – “it’s templates…all the way down! ):

In addition, we have implemented PingPong as a CPP extension to make it easy to integrate into use with PyTorch here (along with a simple test script showing it’s usage):

Finally, for continued learning, Nvidia has two GTC videos that dive into kernel design with CUTLASS:

- Developing Optimal CUDA Kernels on Hopper Tensor Cores | GTC Digital Spring 2023 | NVIDIA On-Demand

- CUTLASS: A Performant, Flexible, and Portable Way to Target Hopper Tensor Cores | GTC 24 2024 | NVIDIA On-Demand

Future Work

Data movement is usually the biggest impediment to top performance for any kernel, and thus having an optimal strategy understanding of TMA (Tensor Memory Accelerator) on Hopper is vital. We previously published work on TMA usage in Triton. Once features like warp specialization are enabled in Triton, we plan to do another deep dive on how Triton kernels like FP8 GEMM and FlashAttention can leverage kernel designs like Ping-Pong for acceleration on Hopper GPUs.