Interactive image segmentation has become a defining mobile experience across the world’s most popular apps. In plain terms, you tap (or draw a rough hint) on an image, and the app instantly “cuts out” the object by producing a pixel mask. This enables familiar features such as creating personalized stickers, isolating a subject for background replacement, or applying selective enhancements to part of an image. If you have used Instagram’s cutouts tool, you have seen how easily object masks can appear directly on your device. These results are powered by compact segmentation models running via ExecuTorch, PyTorch’s open source on-device inference runtime, and Arm SME2 (Scalable Matrix Extension 2).

This blog explores how these hardware and software advances are enabling up to 3.9x speedup for image segmentation in SqueezeSAM, the on-device interactive segmentation model behind Instagram’s cutouts feature, and the broad implications for mobile app developers. SqueezeSAM is deployed across Meta’s Family of Apps, as described in this blog post.

Who this post is for: Machine learning (ML) engineers and developers working on on-device AI deployment for mobile and edge devices who want to understand SME2’s impact on inference performance and how to optimize their models using operator-level profiling.

The Rise of On-Device AI on Mobile

As on-device AI grows, a key question is what becomes possible when more capable models can run faster under tight mobile power and latency constraints. In practice, many interactive mobile AI features and workloads already run on the CPU, because it is always available and seamlessly integrated with the application, while offering high flexibility, low latency and strong performance across many diverse scenarios. For these deployments, performance often comes down to how efficiently the CPU can execute matrix-heavy kernels, and what bottlenecks remain once that compute is no longer the limiter.

SME2 is a set of advanced CPU instructions introduced in the Armv9 architecture, designed to accelerate matrix-oriented compute workloads directly on device. We quantify how much SME2 speeds up end-to-end inference in an ExecuTorch and XNNPACK deployment, and then use operator-level profiling to show what improves. New SME2-enabled Arm CPUs feature in the Arm Lumex Compute Subsystem (CSS) for flagship smartphones and next-gen PCs, with a list of SME2-enabled devices available here.

Case Study: Accelerating Interactive Image Segmentation with SME2

We measure the impact of SME2 on end-to-end SqueezeSAM inference latency when running with ExecuTorch and XNNPACK as the backend, which uses Arm KleidiAI optimized kernels to leverage SME2 acceleration.

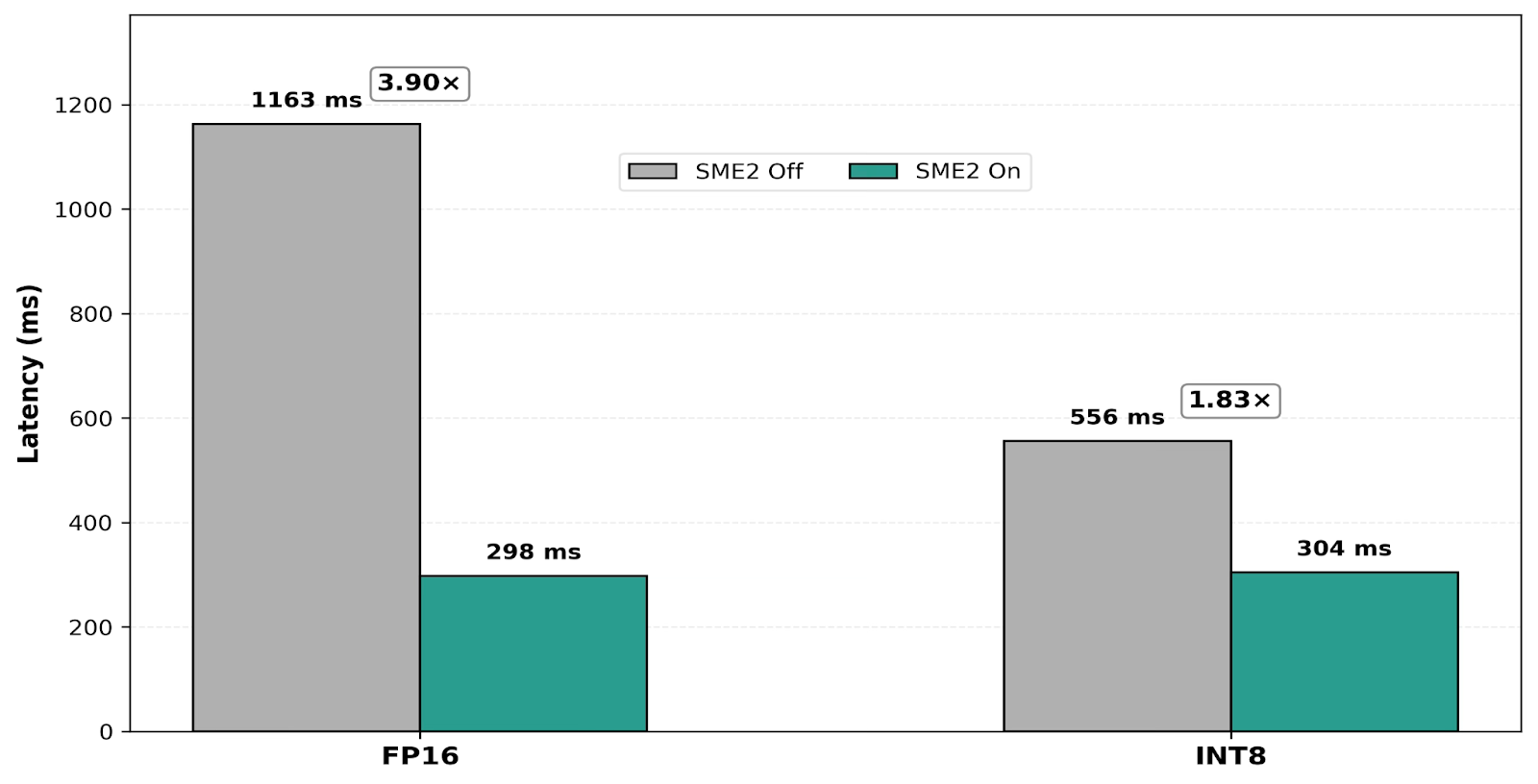

With SME2 enabled, both 8-bit integer (INT8) and 16-bit floating point (FP16) inference see substantial speedups (Figure 1). On a single CPU core with default power settings, INT8 latency improves by 1.83x (from 556 ms to 304 ms), while FP16 improves by 3.9x (from 1,163 ms to 298 ms). Without SME2, these latencies are too high for responsive interactive use; with SME2, end-to-end inference reaches the ~300 ms range on a single core, making on-device execution viable while leaving headroom for the rest of the application.

These results show that SME2 materially accelerates quantized INT8 models on the CPU. At the same time, SME2 enables FP16 to reach latency close to INT8 in this case study, which is notable because it expands the range of practical deployment options rather than replacing INT8. This gives developers more flexibility to choose the precision that best fits their accuracy and workflow requirements, particularly for precision-sensitive workloads such as image super-resolution, image matting, low-light denoising, and high dynamic range (HDR) enhancement. Without this level of FP16 acceleration, mobile deployments are often pushed toward INT8 primarily to meet latency targets, even when that means taking on a quantization workflow and the risk of accuracy degradation.

Beyond benchmark numbers, these speedups translate directly into freed CPU compute headroom. That headroom can be spent on richer experiences, such as running segmentation and enhancement in parallel (for example, denoising or HDR) while keeping the camera preview and UI responsive, or extending cutout from single images to live video cutout with subject tracking across frames, or to reduce power consumption.

Figure 1. End-to-end latency of SqueezeSAM with SME2 enabled and disabled on 1 CPU core in normal mode (default mobile power settings). INT8 improves from 556 ms to 304 ms (1.83x). FP16 improves from 1,163 ms to 298 ms (3.90x), and in this case study FP16 reaches latency close to INT8.

All results in this post are controlled measurements on a vivo X300 Android flagship smartphone with an SME2-enabled Arm CPU. Performance may vary across models, hardware, and specific device settings.

The Stack: PyTorch, ExecuTorch, XNNPACK, Arm KleidiAI, and SME2

How the Frameworks Connect

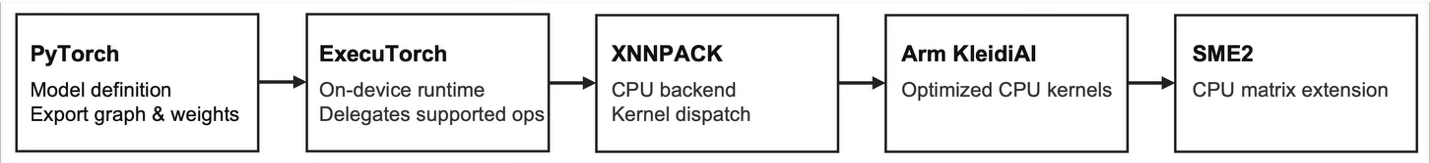

The diagram above summarizes the CPU execution stack used in this case study. A model is defined in PyTorch, exported and run by ExecuTorch, and CPU compute is delegated to XNNPACK as the backend. XNNPACK uses Arm KleidiAI, Arm’s lightweight library of optimized CPU kernels for accelerating ML workloads on Arm CPUs. These kernels can automatically leverage SME2 on supported devices, while also providing optimized implementations for other CPU features on non-SME2 systems.

When ExecuTorch runs a model with XNNPACK delegation enabled, XNNPACK selects the appropriate kernel implementations at runtime based on the capabilities of the underlying hardware. On SME2-enabled devices, this allows the matrix-multiply computation within these operations to benefit from SME2 acceleration without any changes to the model architecture or application code. Once these operations are accelerated, other parts of the inference pipeline, such as data movement, layout conversions, and non-delegated operators, often become the next bottlenecks. This is why operator-level profiling is essential for understanding end-to-end performance.

The Case Study Model

For our evaluation, we use SqueezeSAM which uses a lightweight, conv2d-heavy UNet architecture that is representative of many mobile vision models.

The model structure naturally maps into two major categories of work that strongly influence end-to-end inference time:

- Math-intensive operations: Convolutions (iGEMM, implicit General Matrix Multiply) and attention/MLP layers (GEMM, General Matrix Multiply)

- Data movement operations: Transposes, reshapes, and layout conversions

Platform note: On many devices built on the Armv9 architecture, SME2 is implemented as a shared execution resource across CPU cores, and its scaling behavior can vary by system-on-chip (SoC) and CPU microarchitecture. We account for this explicitly in our evaluation and discuss its impact when interpreting single-core and multi-core results.

Results: INT8 and FP16 (1 CPU core vs 4 CPU cores)

We benchmark the same model in two precisions (INT8 and FP16) with SME2 enabled and disabled. We focus on single-core execution, where SME2 provides the largest relative benefit, and also report four-core results to illustrate absolute latency and scaling behavior when SME2 is a shared hardware resource. All measurements report model-only latency.

The model was executed using ExecuTorch on an Android smartphone with SME2 enabled and disabled under identical software and system conditions. Unless otherwise noted, results reflect steady-state performance without thermal throttling.

All results are reported as Normal mode | Unconstrained mode (ms). Normal mode corresponds to the default mobile power settings with system power policies enabled, representing typical end-user behavior. Unconstrained mode corresponds to a powered, stay-awake configuration in which CPU frequency caps are effectively removed; for single-core measurements, Unconstrained mode results are pinned to the highest-performance (Ultra/Prime, 4.2 GHz in this case) CPU core.

Across both modes, SME2 exhibits consistent relative speedup trends, indicating that its benefits are robust to system power policy, even though absolute latency differs. Unless explicitly stated otherwise, the remainder of this post focuses on Normal mode results, as they better reflect user-perceived latency under typical smartphone operating conditions. Unconstrained mode results are included to illustrate performance headroom and hardware limits and should be interpreted as best-case behavior rather than expected day-to-day end-user experience.

| Precision | Cores | SME2 Off (ms) | SME2 On (ms) | Speedup |

| INT8 | 1 | 556 | 334 | 304 | 172 | 1.83× | 1.95x |

| 4 | 195 | 106 | 180 | 104 | 1.08× | 1.03x | |

| FP16 | 1 | 1,163 | 735 | 298 | 173 | 3.90× | 4.26x |

| 4 | 374 | 176 | 193 | 124 | 1.94× | 1.42x |

Table 1. End-to-end latency results for SqueezeSAM with SME2 enabled and disabled on an Android phone, measured on one CPU core and four CPU cores (model-only latency). Values are reported as Normal mode | Unconstrained mode.

Note on four-core scaling: The smaller speedup on four cores (for example, 1.08x for INT8 versus 1.83x on one core normal mode) is consistent with SME2 being a shared resource, along with other shared system effects such as memory bandwidth and cache behavior. Scaling characteristics can vary by SoC and CPU implementation. In production deployments, one to two cores may be preferred for power efficiency if latency targets are met, while additional cores can be used when lower absolute latency is required and the power budget allows.

Why Operator-Level Profiling Matters

End-to-end latency tells us how much performance improves, but not why, or what to optimize next. To understand where SME2 delivers its gains and what becomes the next bottleneck, we use operator-level profiling.

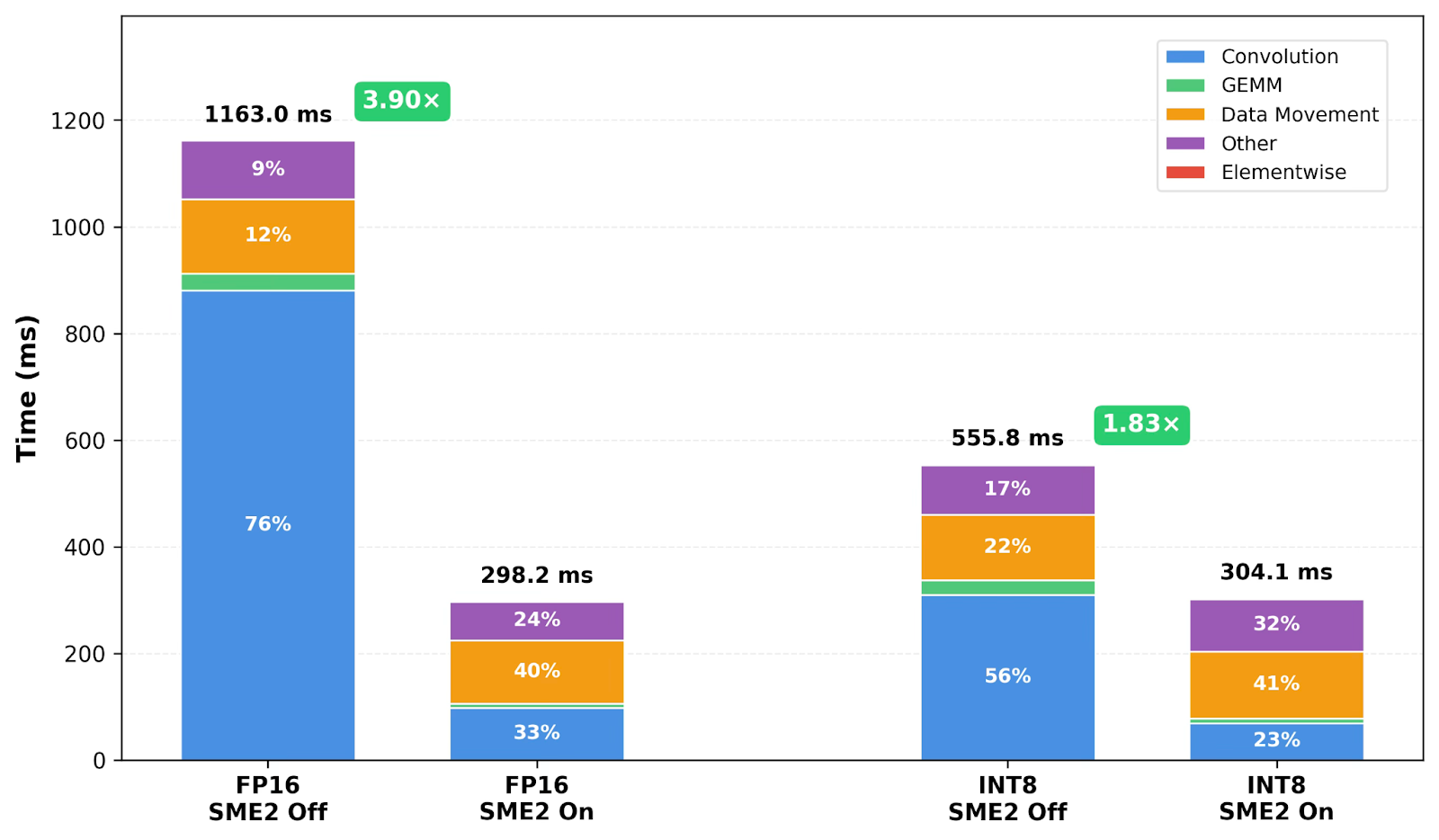

We collect per-operator timing information using ETDump, a profiling tool in ExecuTorch DevTools that records execution time for individual operators during inference. This allows us to attribute end-to-end speedups to specific parts of the model, as shown in Figure 2 and Table 2.

To keep the analysis actionable, we group operators into a small set of categories that map cleanly to common model structure:

- Convolution: Conv2d layers (typically implemented using iGEMM)

- GEMM: Matmul and linear layers (attention and MLP projections)

- Elementwise: ReLU, GELU, Add, Mul, and other pointwise ops

- Data Movement: Transpose, copy, convert, reshape, and padding

- Other: Non-delegated operators and framework overhead

With this breakdown in place, we can explain where SME2 helps most and what remains once matrix compute is accelerated.

Figure 2. Operator-category breakdown (absolute time) for FP16 and INT8 with SME2 enabled and disabled on an Android smartphone (1 Arm CPU core, default mobile power settings). SME2 sharply reduces Convolution and GEMM time, and Data Movement becomes a larger share of runtime.

| Category | INT8 SME2 Off (ms) | INT8 SME2 On (ms) | INT8 Speedup | INT8 % (On) | FP16 SME2 Off (ms) | FP16 SME2 On (ms) | FP16 Speedup | FP16 % (On) |

| Convolution | 309.7 | 69.8 | 4.4× | 23.0% | 881.2 | 98.1 | 9.0× | 32.9% |

| GEMM | 27.3 | 8.1 | 3.4× | 2.7% | 31.6 | 7.6 | 4.1× | 2.6% |

| Elementwise | 2.1 | 2.2 | 1.0× | 0.7% | 1.6 | 1.7 | 0.9× | 0.6% |

| Data Movement | 123.0 | 125.8 | 1.0× | 41.4% | 139.0 | 119.1 | 1.2× | 39.9% |

| Other | 93.7 | 98.2 | 1.0× | 32.3% | 109.6 | 71.7 | 1.5× | 24.0% |

| E2E | 555.8 | 304.1 | 1.83× | – | 1,163.0 | 298.2 | 3.90× | – |

Table 2. The operator-level breakdown for INT8 and FP16, with SME2 off vs on (Android phone, one CPU core in default mobile power settings). Non-matmul operators are affected mainly by runtime variation.

Three Insights from End-to-End and Operator-Level Results

Insight 1: SME2 Accelerates Matrix Compute, Shifting the Bottleneck to Data Movement

SME2 materially reduces end-to-end latency for both INT8 and FP16. On a single Arm CPU core, INT8 improves by 1.83x (556 ms to 304 ms) and FP16 by 3.90x (1,163 ms to 298 ms). Even on four cores, SME2 significantly reduces FP16 latency (374 ms to 193 ms). These gains move single-core execution into the ~300 ms range, making interactive on-device execution viable while preserving CPU headroom for the rest of the application.

Operator-level profiling shows that SME2 sharply accelerates matrix-heavy operators. With SME2 disabled, Convolution and GEMM dominate inference time, accounting for 55.7% of INT8 runtime and 75.8% of FP16 runtime. With SME2 enabled, these operators accelerate by approximately 3–4x for GEMM and 4–9x for Convolution/iGEMM, which is the primary driver of the end-to-end speedups.

Once matrix compute is accelerated, the relative cost of data movement and framework overhead increases, shifting where further optimization effort should be focused.

Insight 2: Transpose-Driven Data Movement Accounts for ~40% of Runtime

After SME2 acceleration, Data Movement becomes one of the dominant runtime components. In the INT8 SME2-enabled run, Data Movement accounts for 41.4% of total runtime (FP16: 39.9%). ETDump traces indicate that roughly 85% of Data Movement time comes from transpose operators, with just two transpose node types consuming over 80% of this category.

This overhead is driven by layout mismatches across different parts of the model and runtime, rather than by arithmetic intensity. In practice, this arises when operators with different layout preferences are composed in sequence, forcing repeated NCHW↔NHWC conversions. In this model, we see normalization executed as a portable NCHW operator in contexts where it cannot be fused into adjacent convolutions (for example, when a non-linear activation sits between Conv2d and BatchNorm), while XNNPACK convolution kernels prefer NHWC. This leads to repeated layout transforms within the UNet encoder–decoder blocks:

BatchNorm/GroupNorm (NCHW) → Transpose (NCHW→NHWC) → Convolution (NHWC) → Transpose (NHWC→NCHW) → BatchNorm/GroupNorm (NCHW)

Because this cost is driven by model and runtime layout choices, rather than arithmetic intensity, profiling is essential to surface it and make it an actionable optimization target.

Importantly, this profiling insight has already proven actionable. As an initial step, we implemented a targeted graph-level optimization in ExecuTorch to reduce unnecessary layout conversions around normalization. In our experiments, this yields an additional ~70 ms (23%) latency reduction for INT8 and ~30 ms (10%) for FP16, on top of the gains from SME2.

These results confirm that transpose-heavy data movement is a meaningful optimization opportunity, and that further improvements are likely as we continue to analyze layout behavior across the graph. Broader findings and their impact will be presented in a follow-up post.

Insight 3: With SME2, FP16 Approaches INT8-Class Latency in This Case Study

Although INT8 uses half the memory bandwidth per tensor element, this does not automatically translate into a proportional end-to-end speedup. With SME2 enabled, FP16 achieves latency close to INT8 in this case study (298 ms vs 304 ms on one core).

The operator breakdown explains why. FP16 sees especially strong Convolution acceleration (9.0x versus 4.4x for INT8), which compensates for INT8’s memory efficiency. At the same time, INT8 matrix paths carry additional overhead from quantization, scaling, and more complex kernel dispatch logic, which reduces the effective bandwidth advantage of INT8.

The net result is that SME2 expands the range of viable precision choices. INT8 remains an effective option, while FP16 becomes more practical for precision-sensitive workloads where quantization complexity or accuracy trade-offs are undesirable. While FP16 approaches INT8 performance in this case study, this behavior is workload-dependent and can vary with operator mix, tensor shapes, and memory pressure.

Hands-On Example: Reproducing the Workflow

To try this workflow yourself, we provide a hands-on tutorial using the open-source SAM-based model, which walks through exporting a model, running inference with SME2, and using operator-level profiling with ETDump. Full setup instructions and code examples are provided in this code repository and learning path.

What you will learn:

- How to export a segmentation model to ExecuTorch with XNNPACK delegation enabled

- How to build and deploy the model to SME2-enabled Android, iOS and macOS devices

- How to run ETDump profiling to collect per-operator timing information

- How to identify and quantify data movement and other non-math bottlenecks in your own models

Conclusion: What SME2 Changes in Practice

In this SqueezeSAM case study, SME2 delivers substantial on-device CPU speedups for both INT8 and FP16, materially changing what is practical for interactive mobile workloads.

What this means for developers and product teams:

- On-device ML becomes more feasible on the CPU: SME2 enables up to a 3.9x end-to-end inference speedup, reducing single-core latency from over one second to roughly 300 ms on a real interactive mobile model under default Android power settings. This shifts CPU-based on-device ML from marginal to practical for interactive workloads, while preserving headroom for the rest of the application.

- FP16 becomes a more viable deployment option in some cases: By substantially accelerating FP16 and narrowing the latency gap to INT8, SME2 gives developers more flexibility to choose the precision that best meets accuracy, workflow, and latency requirements, particularly for precision-sensitive workloads.

- Saved compute headroom enables richer experiences: The freed CPU budget can be reinvested in additional on-device features, such as running segmentation alongside enhancement (for example, denoising or HDR), or extending cutout from single images to live video with subject tracking across frames.

- Profiling reveals the next optimization target: Once SME2 accelerates matrix-heavy operators (Convolution/iGEMM and GEMM), bottlenecks often shift toward data movement and non-delegated operators. Operator-level profiling with ETDump makes these costs visible and actionable.

Two concrete takeaways, depending on where you are starting:

- If you do not ship on-device ML today, SME2-enabled CPU acceleration can make mobile CPU deployment a viable first step for math-heavy models, with profiling providing a clear path to validate performance and iterate.

- If you already ship on-device models, SME2 can create headroom to expand features and improve user experience, while profiling highlights the highest-impact next changes (for SqueezeSAM, transpose-driven layout conversions account for roughly 40% of total runtime).

Together, SME2 acceleration and operator-level profiling provide a practical workflow for both unlocking immediate performance gains and identifying the highest-impact next optimizations for on-device AI.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the Meta ExecuTorch team Bilgin Cagatay, Mergen Nachin, Digant Desai, Gregory Comer, and Andrew Caples for their guidance on real-world use cases and their contributions to inference optimization implementations. We also thank Ray Hensberger, Ed Miller, Mary Bennion, and Shantu Roy from Arm for their support and guidance throughout this work.